The Help — Jackson, Mississippi, Tuesday, June 11, 1963:

In The Help, Kathryn Stockett’s acclaimed novel, this has been a long, tough day for Aibileen, a maid and the book’s primary protagonist. She’s kept late at work. She catches the last bus, but it stops unexpectedly — something’s up, a disturbance ahead. The driver makes the two “colored” passengers get off. It’s after midnight. Aibileen’s frightened. She heads to her friend Minny’s house instead of home. She stumbles in. The radio’s blaring. Minny’s five kids are still up, huddled around the scratchy radio with their mother.

Then comes the horrible news: Medgar Evers, local head of the NAACP had been shot . . . on his front doorstep in sight of his wife, Myrlie and their three kids.

They listen on. The announcer says Medgar Evers has died.

They listen on. The announcer says Medgar Evers has died.

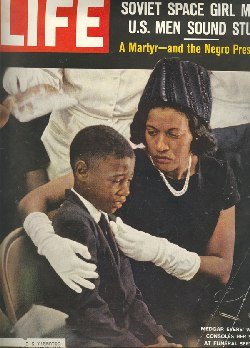

Evers’ assassination sparked outrage in Jackson and around the country. Like children being assaulted with police dogs and fire hoses in Birmingham, the photo of Myrlie Evers and their son at her husband’s funeral became an iconic image documenting a long, hot summer of Civil Rights events.

The nation followed Evers’ funeral train from Jackson to Washington D.C. where Medgar was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. President Kennedy invited Myrlie to the White House. She was on the cover of Life Magazine.

Up to this point, The Help is a story of maids in Jackson — the national Civil Rights Movement only briefly alluded to in an occasional passing sentence. But Medgar Evers is a local, and his murder a personal tragedy: Aibileen knows Medgar’s wife Myrlie; they had met in church.

With Medgar’s death, The Help takes on a larger message . . . Aibileen and Minny realize they, too, have a role to play in the greater Civil Rights Movement. It cements their resolve to cooperate with Skeeter to tell the stories of black maids working for white families.

Meanwhile, out in rural Colorado, in my novel, Soda Springs: Love, Sex, and Civil Rights, Rick Sanders doesn’t learn of Evers’ murder until Saturday, June 15. It’s a tiny story about the funeral, buried on page 11 of the Denver Post.

Rick doesn’t know Medgar Evers, nor Myrlie , not personally, but he knows of him. He had heard Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth preach in Birmingham, Alabama, over spring break in April. He had met Dr. King face-to-face at 16th Street Baptist Church. He had committed his summer to preaching MLK’s message to his hometown.

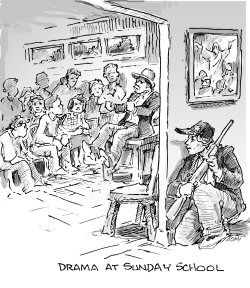

The Denver Post article convinces Rick and his buddy, Ginny Sue (soon to be lovers), their plan to lecture on Negro poverty in Ginny’s youth class at United Methodist tomorrow morning is crazy –- way too boring for high school kids. They gin up a better idea: bring Medgar Evers’ murder into Sunday School, vividly and forcefully. They’ll reenact it as a skit. That will get the kids’ attention . . . then they can use it to explore racism and discrimination and civil rights

Sunday morning, June 16: Rick and Ginny do their skit -– Rick as Medgar and Ginny as assassin, complete with Ginny’s father’s 30-30! The high school kids go wild. Discussion ensues.

Sunday morning, June 16: Rick and Ginny do their skit -– Rick as Medgar and Ginny as assassin, complete with Ginny’s father’s 30-30! The high school kids go wild. Discussion ensues.

But Soda Springs goes berserk –- a rifle in church? My God! In that instant, Rick’s and Ginny Sue’s summer project suffers blows from which they will never recover. Their lives change; the novel changes course.

Same thing in The Help: when Minny and Aibileen react to Medgar Evers’ death as both personal loss and a blow to the national Civil Rights Movement, they commit themselves to Skeeter’s project. In a way, they succeed: they get their book written, and published; Skeeter takes off for a new career with a publishing house in New York City.

In Jackson, life will never be the same for Minny and Aibileen. Nor will it for Rick and Ginny Sue.

Medgar Evers death continues to reverberate through the decades . . . even in fiction.