~ The Rendezvous Log ~

Join our Virtual Caper through the Summer of ’64 for the highlights–and the low points–of A Rendezvous to Remember, a summer we’ll never forget.–

Terry & Ann, authors

Taking the Plunge

Saturday, 16 May 1964, Boulder, Colorado—On this day, 57 years ago, our excursion to Boulder Creek etched an image in my mind that will live forever: Lucky me. I saw Botticelli’s Birth of Venus come to life. —Terry

Aeii, Time’s Running Out!

Tuesday, May 26, 1964, Boulder, Colorado—Time’s running out! Graduation is thundering toward us like a herd of stampeding buffalos, and Annie leaves next week for Europe. I’ve taken her to dinner three times this week—can’t get enough of her. She’ll be gone all summer . . . with that stud lieutenant in Germany. How did we ever get ourselves into this fix?—Terry

A Fine Parting Shot

Friday, May 29, 1964, Boulder, Colorado—It took some cajoling, but Annie has agreed to let me take a glamour shot of her. I told her this was no big deal . . . we’ve shot dozens of pictures of each other for our photojournalism class, capturing close-ups in different moods and different thoughts and experimenting with shadows and light. Her response: “OK, if it’s the Clothed Maja you want me to model and not that au naturel one you’re always raving about.”—Terry

The Perfect Gift of High Fidelity

Monday, June 1, 1964, Boulder, Colorado—I found the perfect graduation gift for Annie. Not a traditional one, to be sure—but a practical one: an AM/FM radio. Snooze button. High fidelity. It even turns itself on in the mornings. Just what she’ll need when she begins teaching this fall in Arizona. She’ll never be late for class. Guaranteed.—Terry

Adieu to Gretchen and my Newborn Niece

Tuesday, June 2, 1964, Boulder, Colorado—Terry and I made a quick trip to Denver for a soft pitch to Gretchen to give up her new daughter—born less than 24 hours earlier—for adoption. I tried to find the right words, me, of all people, weighing in on the future of my brother’s illegitimate child and her mother—after I told myself throughout the spring not to do it. She hadn’t decided whether to keep the child, but regardless, she said she would leave Colorado. Maybe go home to Germany—Ann

On the Road . . . and Left Behind

Thursday, June 4, 1964, Boulder, Colorado—After Annie drove away—headed for a summer with that lieutenant of hers in Germany—I slumped on the steps of Hallet Hall, her dorm. What if he picked up where I’d left off, leaving me to choke in his exhaust?—Terry

Thursday, June 4, 1964, en route to Landshut, Germany—I was caught between an amazing young officer enticing me to join him in Germany as a prelude to a life together, and my closest friend ever, tugging me toward challenging new, but unknown horizons. I felt like a lion tamer in the ring with two hungry lions, warily circling.—Ann

In Germany at Last . . . And at Home in Colorado

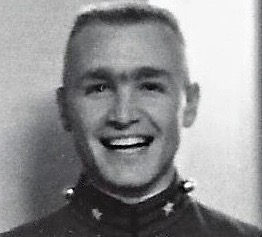

June 10, 1964, en route to Landshut, Germany from the Munich airport—I was a wide-eyed tourist, trying to memorize every detail of the landscape as it whizzed by. Every three seconds I glanced over at this handsome officer. He was doing ninety, my hair whipping about like straw in a cyclone.

He was every bit the man I remembered. A tad more muscular, perhaps. And ruddier. Outdoorsy, a guy who spent time in the sun, but not with the red face and pasty forehead of a rancher. Ramrod straight, square-jawed, so clean-shaven his skin glowed. The hint of a cowlick swirled above his right temple, almost shaved away with his burr cut, but visible nonetheless. And a pointy nose. Not ugly or distracting,

What else will we discover about each other, Lieutenant Sigg?—Ann

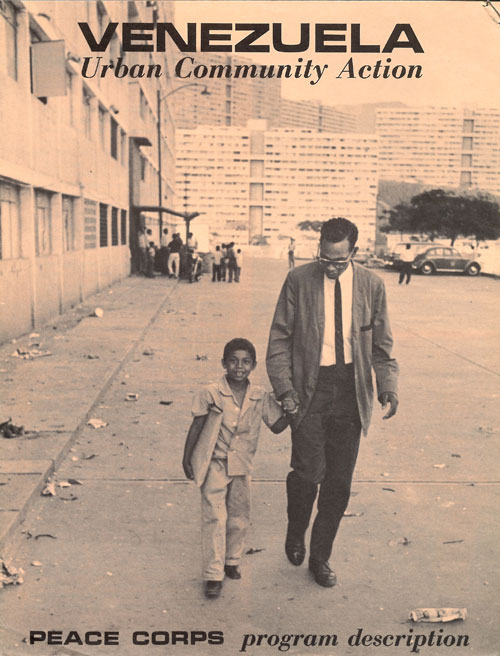

June 10, 1964, Center, Colorado—Home from school, a college graduate at last. For the first time since I was fourteen, I had a summer free. But at what cost? Annie was traipsing around Europe with the dashing lieutenant, and wouldn’t get back to the States until a week after I left for the Peace Corps. It would be more than two years before I’d see her again

Tonight, Annie would be staying in Paris, en route to Germany. I mounted my photos of her in her nightie to my headboard and pretended I was with her in a swanky Parisian hotel room.

That thought kept me panting half the night.—Terry

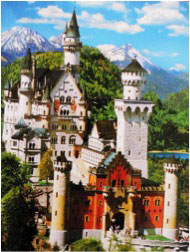

My Bavarian Dreamscape . . . and Alone in the Sangre de Cristos

Saturday, June 13, 1964, Füssen, Germany—I woke up this morning relishing Jack’s good-night kisses. So far, he had exceeded my wildest hopes. Item one: He honored my wishes at the door last night with respect and grace. Item two: He knew so much about Europe, history, music. Item three: He made great choices. Where to go? Neuschwanstein, Linderhof, and Füssen. How to make me feel special? A strawberry tart.

A tapping at my door crept into my reverie, followed by a stage whisper. “Fräulein? Sun’s up. It begs you to help light up my world.”

Oh, yes, Item four: He thinks like a poet.—Ann

Saturday, 13 June, 1964, Sangre de Cristo Mountain Range, Colorado—At Valley View Hot Springs last night, Annie’s image blotted out the starry sky. Emptiness closed in like a mummy-style sleeping bag. With her gone, the road to the Peace Corps at summer’s end threatened to be a lonely trek through a bleak desert. With no shoes. No water. And a full pack of stone-heavy yearnings.

I had planned to spend the weekend at Valley View, hike a trail or two, and attempt an assault on 14,300-foot-high Crestone Peak. But Annie’s likeness called me from every boulder and bush. I abandoned Valley View for the comfort of the farm, hot meals, and a soft bed.

And the hope that each new day would bring me a letter from Germany.—Terry

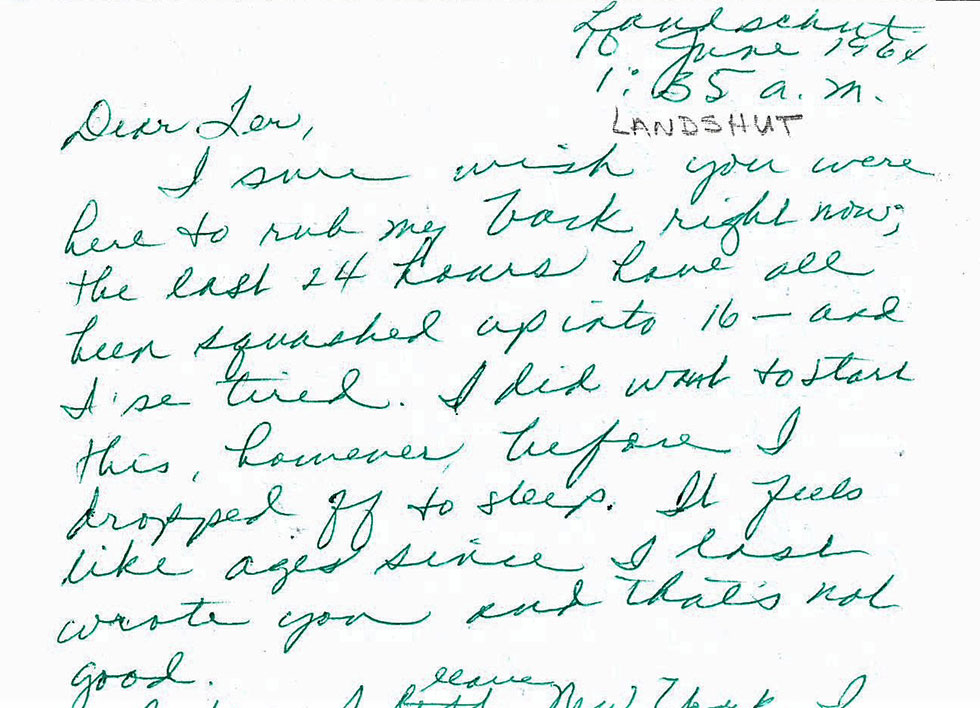

That First Letter from Europe

Thursday, June 18, Center, Colorado—Finally, Annie’s first letter from Europe, “June 10, 1:35 a.m., Landshut, Germany,” three sheets of stationery, hand-scrawled on both sides. “I sure wish you were here to rub my back right now,” she began.

Yeah, me too. Though I’d rub a lot more than that.

Her letter ends with a postscript, two days later: “Friday night, shortly after midnight: I have been far from a mailbox, roaming around in the German boonies.”

Where? Doing what? No hint.

“So much to tell you,” she wrote, but not a word about what it was. Then, another add-on, this one four days later still: “Suddenly went down to the Garmisch area for a few days and didn’t get this finished.”

For a few days? With Jack? By herself? Was it we or I?

“I just got home this evening and happily found your letter waiting,” she wrote.

Only one letter? I had mailed four.—Terry

On the Go: Ann Makes Daring Purchase in Switzerland

Thursday, June 25, Lausanne, Switzerland—Two weeks in Europe, and this was my first day at a beach, Lake Geneva. I’d brought my darling swimsuit, a shimmery one-piece that laid bare my back, with a plunging neckline that betrayed a bit of cleavage but kept my breasts safely in check.

But in Lausanne, even wizened octogenarians and triple-chinned behemoths wore bikinis. Only trouble was, I had never, ever worn a bikini. Now, in a department store changing room, I glared at the image of a girl who looked a lot like me, wearing a Day-Glo yellow hint of a bathing suit.

After a hasty exit from the dressing room, I bought a bikini, a real one, skimpy enough to make me blush. But black, a please-don’t-notice-me black. I couldn’t loosen up for one of those bright scraps of stretchy cloth and string shouting “Feast on these goodies” that the European beauties pranced around in.

I mailed my third letter of the week to Terry the next morning, a feat that left me both pleased and hobbled by a nagging fear that I had forsaken my sense of common decency. I was in Europe visiting Jack and thinking about Terry. I had seen girls juggle more than one guy at CU and thought them contemptible. Now, I was dancing in the same soiled slippers.—Ann

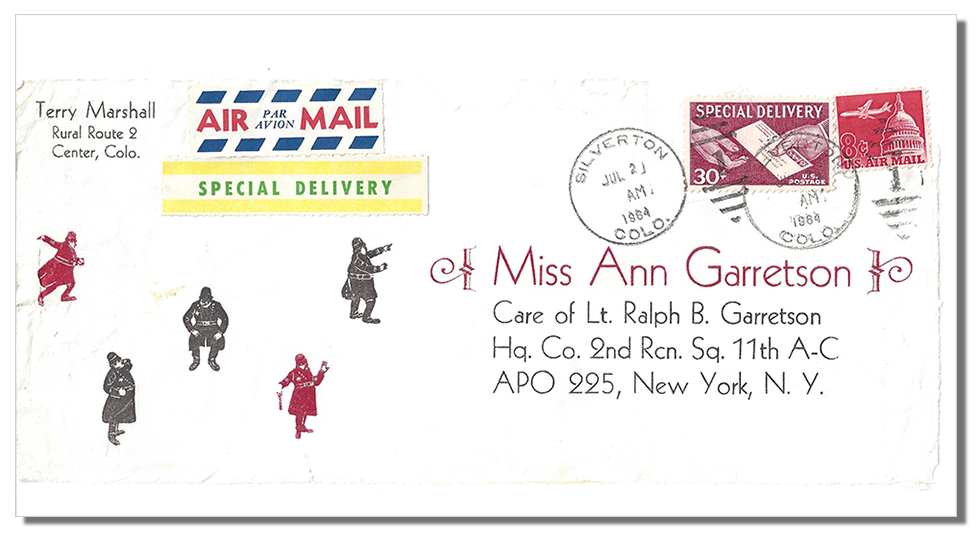

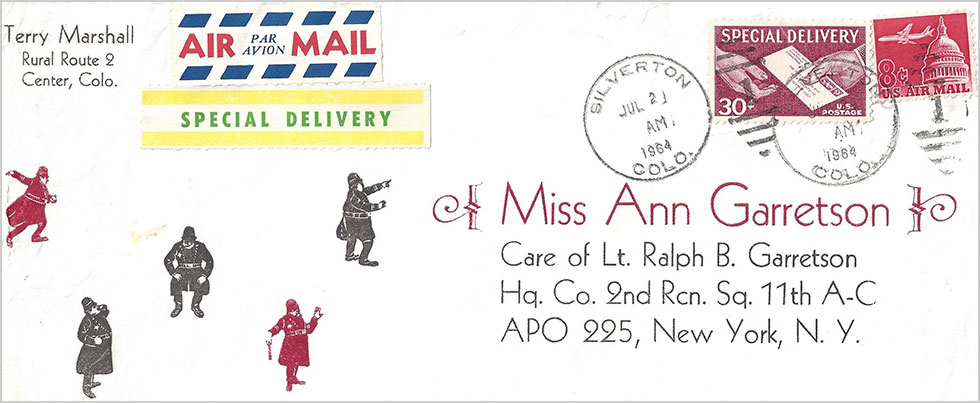

On the Go: Terry Flees to Silverton

Thursday, June 25, 1964, Silverton— At home in Center, I’d been idling away the days, Annie’s absence feeding my loneliness, waiting for summer’s end so I could flee to Venezuela. Enough!

I couldn’t face another empty mailbox. I took off for the solace of Silverton.

Friday, I pulled an all-day stint at the hand-fed letterpress at the Silverton Standard, knocking out an order of 2,500 envelopes and letterheads. I also printed up twenty-five envelopes addressed to Annie in care of her brother in Germany—in red and black ink, which meant having to scrub the press rollers after printing the black, re-ink them, and hand feed each envelope through again, scrub off the red, and re-ink the rollers in black. I jazzed up the envelopes with five one-inch-high dingbats, each depicting an 1880s policeman in a different pose.

Ha, everyone in Germany would know Annie had a guy back home.—Terry

A Cozy Chalet On the Road to Paris

Tuesday, June 30, 1964, en route to Paris—Late that afternoon, near Strasbourg, France, Jack turned into a wooded area and stopped for the night by a small, grassy-banked lake.

Shortly before dinner, he ambled over to the Sting Ray, took out a tent, and set it up.

It was teeny—space enough for the two of us only if we were on top of each other. Outwardly, he was all business, but I sensed a sinful smile lurking beneath the façade.

“A one-man tent?” I asked.

“Negative. One-man, one-woman. You said you like ‘cozy.’ Your letter, remember? Something worrying you?” He looked at me deadpan.

I had only myself to blame. After I had written about my camping trip with Terry, Jack proposed camping with me when he got home from Germany. He’d gone on a quest to find “two single sleeping bags that zip into one double.”

He rolled the sleeping bags into the tent, laying them out side by side. Wall to wall, overlapping by at least a foot. “There. Plenty of space.”

I stood there mute.

He frowned. “What’s wrong?”

I wasn’t ready to “go all the way,” and tonight would put restraint to the test. How could I make him understand that unfettered sex was out of bounds, without throwing a wet blanket on our romance? “Well, jeez, we’re still getting acquainted, you know. I’m a little anxious.”

“You’re anxious? I haven’t slept ever since your first letters mentioned your friend Terry. Are you really serious about this guy?”—Ann

From Silverton: So Who’s Afraid of Audie Murphy?

Tuesday, June 30, 1964, Silverton, Colorado— I thought Silverton would ease the aching loneliness of life without Annie. It didn’t. It merely forced me to face the truth: I couldn’t live without her. But she was merrily globe-trotting through Europe with her dashing lieutenant. The all-American Boy Scout. Audie Murphy in the making.

Still, I wasn’t about to give up, especially to some guy who was as much myth as macho man. I had to beat this guy. And by airmail, not hand-to-hand combat.

I settled into my friend John Ross’s second-story corner apartment on Greene Street, got out my typewriter, and stared out at Kendall Peak for inspiration. Damn! Images of Sarah and Rachel cavorted on the mountainside like sprites. I had blurted out everything to Annie about my nights with both women, every sordid detail, the kinds of details that guys with common sense keep under lock and key and buried in underground vaults.

What a numbskull I’d been! This was going to be like conquering Mount Everest. Alone. In shorts and a T-shirt.—Terry

Paris Blues: A Spat at the Louvre

Friday, July 3, 1964, Paris—The Louvre loomed cold and uninviting. Its stone exterior and granite public square made a drab welcome.

Inside, I couldn’t possibly remember all the masterpieces Terry insisted I see. Nor could I relay his suggestions to Jack. Yet fewer than twenty minutes after we began the tour, as I circled the Venus de Milo, I blurted, “Terry said we should study this piece from every angle to get the full impact.”

Jack’s pained look stopped me short. He stood as frozen as the sculptures around us.

“Oh, Jack, I’m so sorry. I didn’t—”

A muscle in his jaw twitched. I bowed my head against his arm. He jerked it away.

After the tour, we circled back to the Mona Lisa, pushing into the crowd to get a closer look. Jack muttered, “I know why she’s smiling.” His first words since my thoughtless remark.

I cocked a cautious eye toward him. “You do?”

“She has two suitors. If one doesn’t work out, she can reel in the other, just like—”

It hit me like a blow to the jaw. Or was he trying to be funny? “You keeping score? If you are, you’re way ahead.”

We clumped our way back through the Grand Gallery, side by side, but not together. I ground to a halt. “Neither of us wants this. We need to talk. Let’s go outside.”

“Only the two of us? No third-party rivals?”

“I can promise not to bring him up again. How about you?”

“Of course!” He spat it out like a wad of day-old bubblegum—Ann

The Indelible Fourth of July, 1964

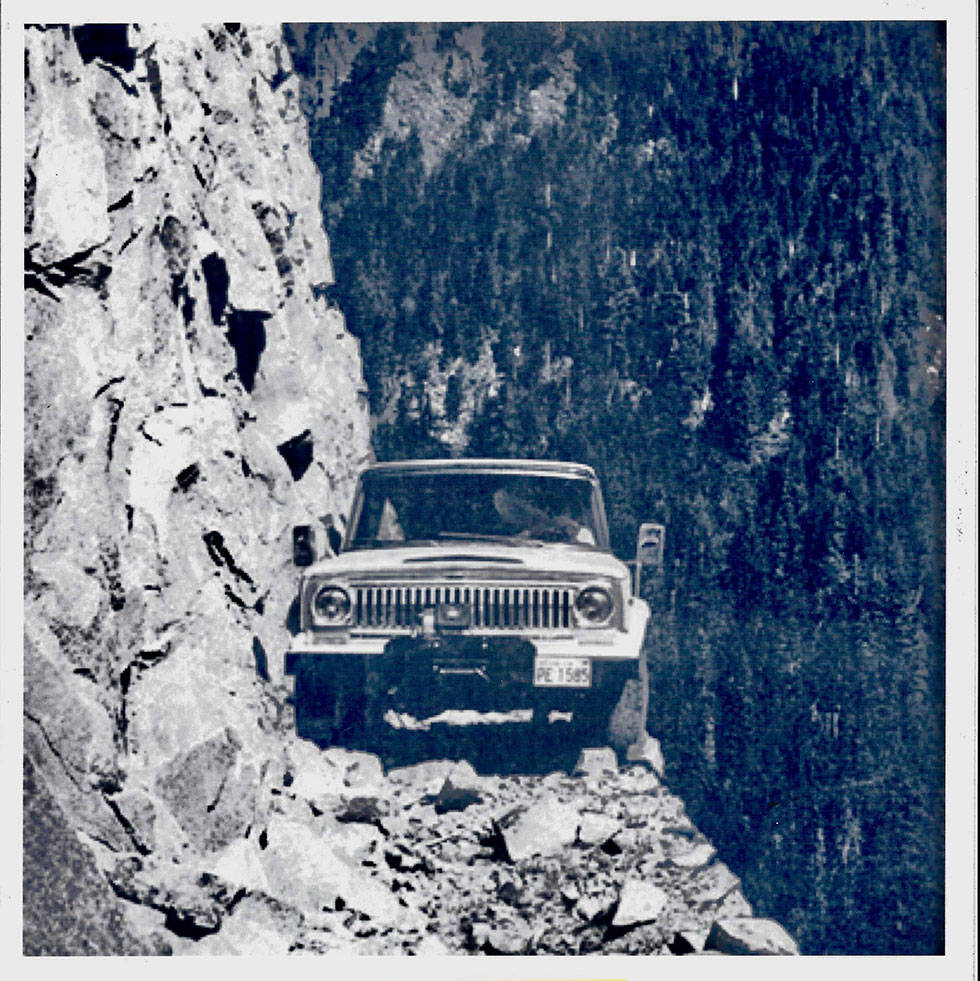

On this day in 1964—July 4— Terry and several friends headed out to master Black Bear Pass, a jeep trail from Silverton to Telluride, Colorado—a trip he vows he’ll never dare to repeat.

That same day, thousands of miles away, my lieutenant and I left Paris and sped toward Saint-Tropez and its famed nude beaches. My day would end in near disaster.

Neither of us knew exactly where the other one was that day, or what the other was doing. Good thing. Had we known, we both would have freaked out. We still do.—Ann

Over the Edge on Black Bear Pass

Saturday, 4 July 1964, Silverton, Colorado. Up at dawn, I chomped down a piece of toast slathered in peanut butter and piled into Allen’s Scout with Roger and Ann-Marie and their friend Janet on a long-anticipated attempt to conquer Black Bear Pass, the heart-stopping backdoor entry to Telluride.

We planned to celebrate the Fourth where few dared to go—a grand alternative to pining for Annie. Or worrying that she and Jack were on their “Grand Tour,” whizzing along to Paris, Corvette top down, her hair flying, his hand creeping up her thigh.

A hand-carved wooden sign at the beginning of Black Bear Pass warned us: “Telluride, City of Gold, 12 miles, 2 hours. You don’t have to be crazy to drive this road—but it helps. Jeeps Only.” We had something better—a Scout 80. We snapped photos of each other mugging the sign, declared ourselves crazy, and took off.—Terry

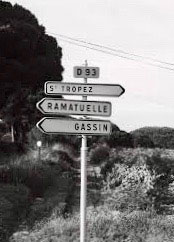

Bumps on the Road to Saint-Tropez

Saturday night, July 4, 1964, en route from Paris to Saint-Tropez. Jack had fallen asleep by the time darkness closed in. Good, he needed the rest.

When I turned from the main highway onto the road to Saint-Tropez, it quickly became a skimpy, two-lane, twisty byway through scrub-brush-covered mountains, sprinkled with intermittent stands of trees. I loved whizzing around curves through a tunnel of headlights. It kept my senses on full alert.

The map had indicated a turn onto a secondary road, and I searched the darkness for road signs. Not a one. Suddenly, a cluster of white signs sailed past. I rolled to a stop. Slowly, carefully, I backed up.

Sk-e-e-e-e-e-e-r-thunk! The car tilted wildly and thudded to a stop. Headlights played off the treetops. No road. I was jerked onto my back, the steering wheel now above me.

“What? Where are we?” Jack’s face lurched into view.

“I . . . I missed the turnoff.”

Dead silence. No engine hum. No wind buffeting the car. But I could hear a steady thumping, louder and louder in the dark. My heart pounding.

“We’re upside down!” Jack shouted. “What the hell happened?”—Ann

Uh-Oh: Teenage Tales Return to Haunt Me

Thursday, July 9, 1964, Verona, Italy. At Lake Garda Jack ushered me into a little rowboat as if it were the Queen Mary. He rowed effortlessly. What a specimen—strong, but not a misshapen weight lifter. For him, it wasn’t a chore, but life at its best. By the time he paused, we were several hundred yards from shore. The sun worshipers and splashing kids were dots on the distant beach.

Jack locked in the oars and flashed an impish grin. “Okay, my dear, I’ve been looking forward to this forever. Ready to go skinny-dipping?”

Uh-oh. In a foolish moment during our correspondence, I’d regaled him with my high school skinny-dipping caper. He teased me in letters, telling me he’d found the “perfect cove” or the “ideal pond” and could hardly wait “to relive 1956 with you.” A fourteen-year-old’s lark with her girlfriends withered next to the thought of 22-year-old me swimming naked with my 26-year-old lieutenant. I wasn’t a kid anymore. Nor was he.

“Last one in is an old fuddy-duddy,” Jack said.

I bit. We tumbled out of the boat in our swimsuits, not bare butt after all. I struck off swimming. When I looked back, Jack was treading water, waving me back. “No, wait! You forgot something.”

I looked at him quizzically.

“It’s ’56 all over again. We’re skinny-dipping, remember? First, into the water, next off with the suits. Wasn’t that how your story went?”—Ann

Angst over Test-Driving a Honeymoon in Europe

Thursday, 9 July 1964, en route from Colorado to California. We had left Center at dawn on Wednesday. Taking turns, Mom, Pam, and I drove 700 miles the first day, all the way through the Colorado and Utah mountains to Ely, Nevada.

Today, we racked up 500 more miles and arrived wobbly kneed at my cousins’ place late this afternoon. I spent half the time thinking about Annie.

A week before, I’d asked her to marry me, but I mailed my proposal July 1, the day after she left Germany. She hadn’t gotten any of my letters from Silverton. She didn’t know I was madly in love with her. Worse, that West Pointer was test-driving a honeymoon, chauffeuring her through Europe, romancing her every minute of every hour of every day.

Before we left Center, I had started a new letter to her, getting right to the point: “One thing that really bothers me is the thought of him touching you, kissing you. I can’t dwell on that. It’s too unpleasant.”

I tried not to think about it. But I couldn’t stop. Equally excruciating was the likely fact that I wouldn’t see her for two years.—Terry

Last Night In Venice: Is This “The Night”?

Sunday, July 12, 1964, Venice. No camping in Venice, so a hundred strides off the Piazza San Marco, we had found a tiny pensione with finely carved furniture, a canopied four-poster bed draped in antique organza, and private bath, with breakfast—all for a hair under five dollars a night.

This evening, after two full days of sightseeing, we wound up at the Lido, a slender barrier island between Venice and the Adriatic Sea, where we ate on the beach and watched the dipping sun paint the clouds gold and black over Venice.

As we cuddled on a dawdling vaporetto en route back to Piazza San Marco, tenor gondoliers materialized from the dark, serenading the lantern-lit lovers in their holds. The melodies seemed more romantic wafting across the water at night.

Back at the pensione, the two small lamps with old-fashioned lampshades cast our room in a cozy hue. Jack wrapped his arms around me and whispered, “You know, Venice is the most romantic city of cities. Tell me that tonight’s the night.”

I wanted to say yes, but I couldn’t. “Let’s play it by ear,” I said. “Better yet, by touch . . .”—Ann

Politics In San Francisco: Ho, Ho, Ho, Barry Must Go

Sunday, 12 July 1964, San Francisco. After breakfast, CBS Channel 5 announced a protest march against a predicted win for Senator Barry Goldwater at the Republican National Convention, set to open Monday at the Cow Palace, San Francisco’s convention center.

Cousin Paula and I glanced at each other. We couldn’t resist.

Mom shook her head. “You kids are nuts.”

An hour later, Paula and I plunged into a river of Blacks and fell in behind a guy with a four-year-old on his shoulders and a pregnant wife at his side. We weren’t the only Whites—there were scores—but Whites were clearly a minority.

I’d seen protests only on TV, and in photos of the 1963 March on Washington: Being inside a protest was a new world for me. There were no Blacks in Center—not one. In high school, no team in our league had Black athletes. None. At CU, we only occasionally saw a Black person on campus. A handful starred on the football and track teams, but the basketball squad had only one.

That first step onto Market Street was tough, my heart racing. I glanced furtively at the faces around us. No one frowned or snarled or called me a honky or flipped the bird. This was a meandering crowd of like-minded protesters, nothing to fear.

Paula and I strode along, waving her calligraphy signs like beacons. Hers read “Civil Rights in ’64/Ho, Ho, Ho, Barry must go.” Mine was less flamboyant: “Civil Rights, Yes/Goldwater, No.”

I took Paula’s hand and squeezed it. She beamed and squeezed back. “Me too, cuz. This is great, isn’t it?”—Terry

Into The Bowels Of Communist East Berlin

Wednesday, July 15, 1964, Berlin, Germany. I set off for Checkpoint Charlie, the nexus between the free world and Communism. The guard standing outside snapped his rifle to his right shoulder, his left shoulder, and back to his right, and then he banged his heels together. I slammed to a halt and looked around warily.

Beyond the guard shack, an austere no-man’s-land barricaded East Berliners from West. The barren strip, two hundred feet wide, was studded with waist-high chunks of broken pavement, construction rubble, and those pointy hedgehogs—huge angular obstacles made of catawampus iron I-beams capable of halting a tank in its tracks—like jacks, but on a scale for the children of giants. Tangled barbed-wire fences stretched out of sight in both directions.

Across the divide, a five-story apartment building kept a weary vigil, its bricks in various stages of disintegration. The black-hole windows shouted “Vacant!” But wait, did I detect snipers lurking just out of sight? How many would-be escapees had been shot from those very windows? Did I dare cross this divide?

It was one thing to have seen the endless strip of denuded land that separated sylvan Germany from Czechoslovakia near Jack’s outpost, but quite another to be within sniffing distance of these tough-guy guards at the menacing gap between East and West Berlin. I was beginning to understand why the Cold War was so hot for Jack, Bonner, and their men.

Shaking off my qualms, I strode into Checkpoint Charlie as if I did this every day and bought a one-day visa, then marched into East Berlin and a crash course on “the enemy.”—Ann

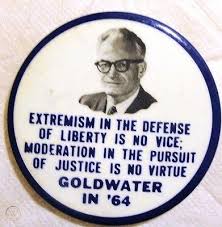

Goldwater’s Call To Arms: “Extremism . . . Is No Vice”

Thursday, 16 July 1964, Los Gatos, California. We were still abuzz over Barry Goldwater’s call to arms last night: “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice!”

In a landslide, the Republican National Convention had anointed Goldwater to oppose Lyndon Johnson for president. His battle cry was no slip of the tongue; he smacked us in the face with it. Pausing after each word, he shouted, “Liberty—is—no—vice!” Delegates applauded, cheered, whistled, and blew air horns in approval—for a thunderous sixty seconds.

Cousin Paula and I shook our heads.

Who decides what’s extreme? Who defines the defenders of liberty and the desecrators? Goldwater had done a backflip into the 1950s. Worse, the “cream” of the Republican Party—delegates from Maine to California—agreed. They leaped up, mounted hypothetical horses, and formed a modern-day posse ready to ride out of the Cow Palace and lynch any American who disagreed with them.

We truly were in for it—a bare-knuckle, spare-no-mud presidential campaign.—Terry

A Letter From Colorado: “Marry Me”

Saturday, July 18, 1964, Landshut, Germany. After dinner and dancing, Bonner walked me back to the teachers’ quarters, angling past his room for my mail. “I shouldn’t have to tell you this again,” he said. “Don’t import your own men when you come to visit me.”

He handed me a bundle of envelopes, all from Terry, all addressed in print-shop font, and as gaudy as circus flyers. Bonner was as steely eyed as a gunslinger, “And don’t break my best friend’s heart.”

I retreated to my room, lined up Terry’s letters, and opened the special delivery one. At the top of the second page, I gasped. “Annie, I am announcing formally and officially that I am proposing to you. I want you to marry me.”

Marry Terry? Now? What about the Peace Corps? I read quickly, determined to finish before tears spilled. Oh, I missed him so much. I did love him. But I loved Jack too.

And tonight, somewhere along the German-Czech border, was the Other Guy—the one who had squired me around Europe for two glorious weeks, the one I would see tomorrow morning. He would read this news in my face. What would I tell him? What would I tell Terry?

A silent scream wracked my insides. I don’t know! Don’t pressure me! Either of you!—Ann

On The Road In California . . . But Thinking Of Europe

Saturday, 18 July 1964, Los Gatos, California. We Marshalls—Mom, Pam, Randy, and I—took off early for northern California to see Mom’s sister, Clarice, an aunt I’d never met. After high school, Aunt Clarice had joined the Women’s Army Corps and got to see a bit of the world. At long last we’d get to meet the mysterious Aunt Clarice, soldier, world traveler.

I pretended that California was as exotic as Europe—to bring Annie’s thoughts back to the US. “You would love Carmel,” I wrote, “no neon, no garish signs or billboards; quaint little shops with quality goods instead of schlock.”

In Eureka, we spent the evening chatting with cousins every bit as delightful as the Kocher gang. Aunt Clarice was at least six feet tall, and Uncle Al at least six-four. I’d never met anyone so tall. Despite hitting it off with the Keister kids, by the time we finally trundled off to bed, I was missing Annie more than ever, and wrote her with a new confession:

“I’ve been hit again with a desire to have children. I can’t think of anything greater than giving you a child we could raise and love and share—in a couple of years after you’ve taught for a while and I’ve gotten my M.A.

“Last week, in Chinatown, I saw some beautiful silk shifts with splits up both sides that I wanted to get for you. I want to marry you, buy you a fancy wardrobe, and just sit around the house admiring you. We’d spend all our money on books and sexy clothing for you (and maybe a pair of socks for me once in a while).”—Terry

To Terry: Something Catches At The Thought Of Marriage

Monday, July 20, 1964, Landshut, Germany. I still had no answer to Terry’s proposal, but I couldn’t postpone a reply any longer.

I wrote, “Silverton, more than any other thing, brings me close to you because it typifies a way of life. The only thing I’ve figured out for sure this summer is that a woman marries far more than a husband. She weds a way of life she must also love.”

I knew I would choose peace and the tranquility of the mountains as a way of life—if I could only cut the powerful sinews that bound me to the military. Could I turn my back on my parents, my brother, and my life so far? That, in a nutshell, was the challenge. But I couldn’t even say it out loud.

I told Terry how he and Jack were so much alike. Why not share the heartache I had subjected Jack to? I had to make Terry understand how difficult the decision was. I asked for more time, promised to call when I could, but concluded, “Somehow, something catches inside me with the thought of marriage right away.”

Before noon, I addressed my letter to Terry in California, marched to the post office, and paid thirty-eight cents for an airmail special delivery response that was totally inadequate.—Ann

To Jack: Your Departure Leaves Me Less Than Whole

Tuesday, July 21, 1964, Landshut. Early morning. A rumbling rattled my room. I knew that smell—diesel exhaust. I stumbled to the window. Across the parking lot, soldiers swarmed the BOQ like an invasion of ants, hauling boxes and duffel bags into belching trucks. Jack’s Sting Ray crawled up a ramp onto an auto transport. I was about to be left alone.

How to say goodbye? There wouldn’t be a time or place for a proper farewell. But what about this: Send part of myself, a lock of hair. The thought yanked me from the window. I penned several versions of my parting note before I lit on this:

“My dearest Jack, Your departure leaves me less than whole, for you are taking part of my heart with you. I know you can’t hold it in your hand when you think of me, so I’m sending this lock of hair that you can see, touch, even sniff (if you’re so inclined—heh), to remind you of our extraordinary summer—and to hold us till Johnstown.

“No matter what happens, part of me will always belong to you. With my deepest love for all you have shared with me, and for the better person I have become by knowing you. Yours, Ann“

For Terry: A Nightmare Lurks in the Mailbox

Saturday, 25 July 1964, Center, Colorado. Late that afternoon, I pulled into our driveway, leaped out, and sprinted to the mailbox. It was packed so tight I had to pry everything out.

I went through the mail like a pirate digging up his loot. Voilà! News from long-lost Annie—I slit the envelope open as delicately as if it were a bomb and a careless motion would trip a trigger and blow my life to pieces.

I flipped first to the end: “I love you, A.” Yes!

I skimmed through. “Jack has not, by the way, proposed.” Thank God!

But then she wrote: “You must know I share wholeheartedly with you the desire to be together this year . . . and yet something catches inside me with the thought of marriage right away. I cannot give you a definite answer right now.”

A nightmare tormenting me for weeks caromed through my mind: Annie and The Stud leap from his Corvette and sprint into an opulent sultan’s tent, flinging off their clothes as they run.

Inside, she’s naked. He’s naked, too—save for his sword, dangling from his red West Point waist sash. They sink into a palatial bed: silk sheets, rose petals, sultry music, flickering candlelight, incense wafting. Instantly, arms and legs entwined, they’re one, more exultant than Rachael and I were in our wildest moments. Argh! I couldn’t stand the thought.—Terry

Ann Asks Herself, “Why Get Married at All?”

Monday, July 27, 1964, Copenhagen. Monday night I squeezed out time to scrawl the long-delayed letter to Terry, telling him that the joy of travel had been diminished by his absence. More importantly, I confessed: “When I returned from Berlin, I thought I wanted to marry you. Then in the last days before Jack left, my feelings toward him did an about-face. Now my emotions are a jumble. I know I shall never love you any less, but Jack has made me reassess my feelings toward him.”

Wednesday, July 29, 1964, hitchhiking from Gladbeck, Germany to Landshut, Germany. These six hours were mine alone. Not Jack’s. Not a time I wished for Terry. I managed a huge challenge by myself and had a memorable adventure at the same time. I was discovering the real me, the girl who was her own person. I could make it on my own.

As I waved goodbye to my new German friends, I asked myself, Why get married at all?—Ann“

Terry: Not a Word from Europe. None!

Wednesday, 5 August 1964, Center, Colorado. I was leaning on a shovel at the ditch bank, pretending to irrigate the spuds, when Mr. Carter slid to a stop at our mailbox. He rooted through the letters, pulled together a bundle, and handed it out the window. “Sorry, son—bills and a newspaper. Nary a stich from Europe.”

Eleven days since I got Annie’s postcard and letters. Nothing since. Zilch. In eight days I’d fly to Berkeley for Peace Corps training. I wanted to call and get a definite yes or no, but I had no idea where she was.

I had replayed my options a thousand times. It was simple. If she said yes, I’d cancel Berkeley, marry her, and move to Arizona. If she said no, I’d bid a teary farewell and take off for Venezuela.

But I had no option for protracted silence.—Terry

Ann: London’s Race of Avoidance

Wednesday, August 5, 1964, London. I was back in the English-speaking world where I could understand and be understood.

Yet in some ways this country was more foreign than Germany or France. Though everything seemed familiar, some things were life-and-death different. Like crossing the street. When I got off the Tube, I spied my hotel across the road. I looked left, and stepped out. A horn blared. Brakes squealed. I whipped my head around. A Jaguar was barreling toward me on the wrong side of the road. He swerved, roared past, and shouted, “Watch where ye’ goin’, Yank!”

A frenzy of sightseeing took me to Buckingham Square, Westminster Abbey, Big Ben, Hyde Park, and Hampton Court. I saw a Shakespeare play at the Aldwych, but it was Merchant of Venice, not Macbeth. Instantly, I was in Venice again—with Jack, my hand in the crook of his elbow.

The torture display at the Tower of London left me queasy. Religious dissidents hung from manacles, stretched on the rack, and crunched like walnuts. Horrifying! I kept moving, faster, faster to escape the grisly specters.

Actually, the real reason I was running like a mad woman was avoidance. I knew I should call Terry, but I couldn’t say the one word he wanted to hear, “Yes (I’ll marry you).”—Ann

The Life-Changing Call From London

Typical British phone booth of that time. Many thanks to Mike for this photo from Pexels.

10 August 1964, Monday, 5:58 a.m., Center.

I was in dreamland, and somewhere in the fog, the damn phone was ringing off the hook. Then clomp, clomp, louder and louder, footsteps tromping up the stairs into my brain.

“Terry, Terry. It’s for you. Long distance,” Mom hollered. “Overseas!”

I stumbled downstairs. “Hello, hello?”

“I have a reverse-charges call for Terry Marshall from”—the woman on the phone had the same stuffy British accent the queen had, and it was six o’clock in the morning, for crying out loud—“Ann Garretson. Will you accept the charges?”

We talk. Annie tells me about all the places she’s visited, all the things she’s seen.

I wanted to tell her how much I loved her, that I could hardly wait to see her, but the boys were leering in, bouncing past, popping into sight again. Mom shouted, “Boys! Git!” Footsteps thumped into the kitchen. The boys tittered and raced past again. I could barely make out what Annie was saying. I couldn’t hold off any longer. I had to ask her, despite all the nosey little ears:

“About my letter. My proposal. Will you? I’ve got to know.”

A sigh. Silence. Then, “I need time. I can’t decide here, like this. I need to spend time with you. Am I still welcome in Center? Could I come?”

“But when? Your mom said you were going to spend some time on the East Coast.”

“I leave for New York on Wednesday. A couple of days there. By the weekend.”

“No, that’s too late. I’ll be in Berkeley on Friday.” Silence again. “You still there?”

“I can’t make it before the weekend, Ter. I really can’t. I promised Jack’s mom in May I’d visit them in Johnstown on the way back. I told you. Remember? Can you call the Peace Corps and go late? Next week sometime?”—Terry

A Western Meadowlark sparks hope. With thanks to Daniel Roberts for this image from Pixabay.

10 August 1964, Monday, Center. I needed a secluded spot to figure out what to do. I grabbed my reporter’s notebook and hiked off for the haystack in the southwest forty.

While my mind whirled, a nearby meadowlark gave me hope with its cheery greeting, chupp-chupp, wheedle-e. I responded. She sang for me, but fell silent. For a while, a magpie perched on a fence post and scolded me for invading his territory—no sympathy from him. A jackrabbit appeared in the rutted roadway, stared, then bounded into the weeds. None of the other thicket dwellers cared about my dilemma—not the busy ants, the stink bug, or the grasshoppers. Or maybe they did, maybe their mere presence helped me realize what I had to do.

I trudged home too late for lunch, made a cheese sandwich, went upstairs, and typed a short letter—a telegram actually—drove to the Western Union office in Monte Vista, and sent a missive to Mr. Clennie H. Murphy Jr., Division of Selection, Peace Corps, Washington, DC:

10 August 1964. Am turning down invitation to Venezuelan project. Will not report 14 August for training in Berkeley. Airline tickets being mailed today to Washington. Apologize for last-minute decision and any inconvenience to you, but feel entering training now would be mistake.

A Bombshell in Johnstown

Wednesday afternoon, August 12, 1964, New York City. Jack swept me up at the LaGuardia gate in a bear hug so powerful I couldn’t breathe. “At last, at long last. How was your trip? As endless as it was for me? Three months? A year?” Question after question. He didn’t pause.

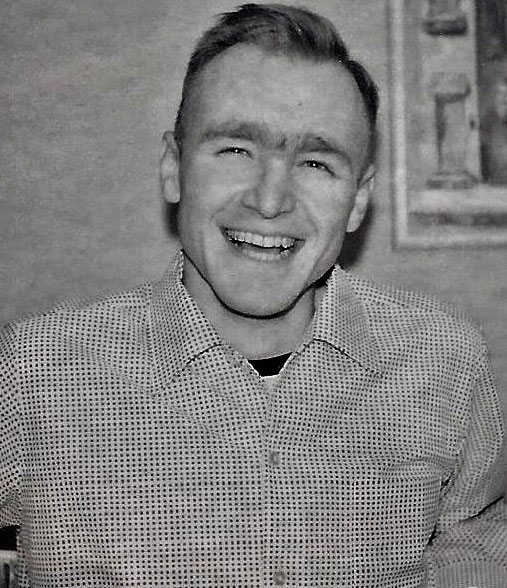

Jack Sigg sharing a laugh

He tucked me into the Sting Ray, and on the way to Johnstown, I introduced him to my Swedish friend Agneta and took him with me on that madcap drive through Germany with the butcher brothers. He roared with laughter over the deodorant caper. “I love your independence, your self-confidence—to set off without being able to speak German.”

What a great listener—nodding, chuckling, eyes intent. I’d pause, and he’d whisper, “What else? Where did you go next?” And “The Thames. Tell me about the Thames. Is it like the Danube? The Rhine? I never made it to London, you know.”

Late that night, at 85 Osborne Street in Johnstown, his mom put her arm around my waist and whisked me upstairs to a slanted dormer room overlooking the backyard. She and Jack’s dad embraced me as if I were their own daughter, returned from distant lands.

Friday night, August 14, 1964, Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Dinner conversation flowed like a mountain stream through our times in Europe—Jack’s two years, our two months. Bud and Peggy Sigg played tag team bringing us up to date on the headlines in America: Mickey Mantle hit a 461-foot homer. President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. Gas hovered at thirty cents. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorized full-scale war against North Vietnam.

Jack Sigg, facing war.

The Gulf of Tonkin! We all fell silent. I exchanged looks with Peggy. Bud turned to Jack. “That resolution sounds serious, son. What do you make of it?”

“It is serious, Dad. I’ve been thinking about duty in Vietnam. I need to do it sometime, might as well be sooner than later.”

He tried to skip it into the conversation like a pebble on a still pond, but it landed like a mudslide, damming the stream of chitchat.

Peggy caught her breath. “Oh, Jack, no! That Tonkin stuff means war.”

“That’s what I’m trained to do, Mom. Can’t shirk my duty.”

My voice puffed out like a whisper into a gale. “But now? I thought we . . . now, Jack?”

Jack focused squarely on me. “I’ve thought about this a lot. Might as well go while I can do some good, before communism spreads its tentacles to another Asian country.”

This wasn’t a spur-of-the-moment conversation stopper. He was a soldier facing war. I leaned in. “So, have you already signed up?”

“Yes. Combat zone duty is essential if I’m going to move up the ranks. I’ll be an adviser to the Vietnamese army. A teacher, not a dogface leading the charge up San Juan Hill.”

Whoa. He had decided. Duty and career first!

Was this a warning shot to me—a tangible illustration of the life of a soldier? And a soldier’s wife? Was he driven to the decision by training and inclination? Or had he concluded things weren’t going to work out for us, and Vietnam duty would put a dramatic end to things? “When do you leave?”

“Early next year. After I finish counterintelligence at Fort Holabird and three months in Monterrey learning Vietnamese. Then Saigon.”

He spoke in a monotone, as if he would divulge no more than name, rank, and serial number.

Conundrum in Colorado

Sunday morning, 16 August, 1964, Center, Colorado. I was up at dawn. I showered, helped Mom fix breakfast, did the dishes, changed my sheets, and tidied my room. It was seven-thirty, still two and a half hours until Annie would get to Alamosa.

I dusted off the Falcon, checked the tires, trimmed my mustache, and brushed my teeth: 8:15. I showered and brushed my teeth again: 8:45. “I better go,” I told Mom at 8:50. “That plane comes in early sometimes.”

The Falcon all cleaned up for the homecoming

“Yeah, you’d better,” she said. “It takes almost half an hour to get to the airport.”

I drove County Line Road at thirty miles an hour to keep from kicking up dust and still got to Alamosa twenty minutes early. The airport was small—one runway, one plane at a time, no coffee or gift shop, a waiting room the size of a doctor’s office.

I spotted the DC-3 circling in from the Sangre de Cristos before the ticket agent did. It zoomed past on the runway, slowed, and crawled back. Greeting this two-engine plane wasn’t new to me—I’d been first on the tarmac before, snapping photos of dignitaries as they stepped out onto the stairs.

This time, I had imagined a grand cinema reunion: We sprint across the tarmac toward each other. She flings herself into my arms. Her legs lock us into a licentious embrace. Our kisses go on forever.

Instead, I stood there like a doofus. “Damn,” I said. “It’s good to see you.”

She shook my hand. “Good day, sir. You look familiar—like an old buddy I used to have.” She eyed my fresh haircut. “Only he was a little scruffier.”

That was Annie, always quick with a smart-aleck retort. I managed a lopsided grin.

Sunday afternoon, 16 August, 1964, Center, Colorado. At home on the farm, we began like skiers inching up a mountain slope, anchoring each step so we wouldn’t slide backward. We chatted under the cottonwoods at Coffman’s pond, hiked the fields, and cuddled atop the neatly stacked alfalfa bales in the southeast forty.

Shadows of disquiet hovered over the farm

We followed the railroad tracks to the old cattle chutes beyond Marshall Produce, and by midafternoon, our words were tumbling out like boulders in the spring runoff. Sometimes speech became impossible because the thousands of saved thoughts log jammed in our brains.

Then we’d kiss. And hug. And off we’d go again—to Paris, Silverton, San Francisco, the Bavarian hills, London Bridge, a lake near Juliet’s house in Verona. And, oh yes indeed, she’d marveled at the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre, as well as the Dürer masterpieces in Munich.

She was the Annie of late May, but with ten thousand new freckles. She had been in the sun. The freckles enhanced her charm—she’d never been an alabaster-skinned Botticelli fit only for a pedestal. She pulsed energy and wielded her wit with epée-like precision. Best of all, she was as responsive to my every touch as she had been in June.

Nevertheless, beyond every joyous affirmation, shadows of disquiet hovered. Each time they swooped in, we artfully dodged. We didn’t acknowledge that marriage proposal of mine—or her non-answer. Nor did either of us dare mention his name, that summer companion of hers.

Teetering From One Precipice to the Next

Monday night, August 17, 1964, Albuquerque. The streetlight illuminated a swath of the aqua wall in my bedroom, along with the flowery bedspread, the vanity mirror, and the matching miniatures of laughing young square dancers, all décor that Mom and I had worked with juicy delight to assemble for my very own room—when I was in sixth grade.

Photo by Elijah O’Donnell from Pexels.

This familiar place had always enfolded me in comfort. But I wasn’t a little girl anymore. The past two days had been a replay of my summer, only this time teetering from one precipice to the next, trying to shield Terry from mention of Jack.

Worse, I had declared my love for Terry as avidly as I had for Jack. I struggled with my behavior these past months, hurling painful words at myself: Tramp. Jezebel. Minx.

On the positive side, Mom and Dad had bent over backward to welcome Terry. And Terry had passed Dad’s jalapeño test—my only boyfriend ever to succeed.

The trouble was, I had never told them he was my boyfriend. Nor that Jack also was my boyfriend.

But they knew I’d traveled Europe with Jack and had visited both Jack and Terry on my way home. They treated Terry as if he were still my buddy while artfully steering the conversation around any mention of Jack. I was grateful for that. But very likely, neither man qualified, in their estimation, to be married to the precious child who used to occupy this girly room.

I didn’t want them dabbling in my decision. What did I want from them? I didn’t know.—Ann

At Least She Hasn’t Said “No”!

Monday night, 17 August 1964, Albuquerque. I couldn’t sleep, not with Annie in the next room in that nightie. I lay there three feet from fifteen-year-old Jimmy, him on night watch, pretending to be zonked out.

Separated lovers: M. Kilhenny/Shutterstock.

Annie and I had spent a day and a half together since she stepped off the plane. We’d talked for hours. The signs were positive. She hadn’t mentioned Sarah and Rachael, my bombastic editorials and the scurrilous letter to Atkins, my left-wing politics, and the fact she was army and I was a conscientious objector.

A few shadows darkened my spirits: her comment that she had never lived alone and that traveling solo had given her a desire to make it on her own. Her chilling declaration: “Maybe I’m not quite ready for marriage.”

But I couldn’t help dismissing those as footnotes, not key themes. Her passion far outweighed her doubts: the lingering kisses, embraces, touches.

Despite my best efforts to remain hopeful, a menacing chimera lurked under my bed in Jimmy’s room—that lieutenant she had left behind in Germany.

On the way to Albuquerque, I had dared ask Annie if he had proposed. Her eyes narrowed. Whiffs of smoke curled up and singed the roof of my car. “No, he didn’t,” she said at last, her words icy. “But, yes, we had some great times together.”

For a week, I had worried I had blown it by turning down the Peace Corps, that she’d come back, reject me, and all I’d have would be shattered dreams. Now, there I was, ready to take off in the morning for Phoenix to find a job so we could be together.

She hadn’t said yes, but more importantly, she hadn’t said no.—Terry

Ann: The Reluctant Fashion Plate at Glendale High

Wednesday morning, August 19, 1964, Albuquerque. At last, a day to myself. No Terry. No Jack. I stretched, turned over, and was about to drift back to sleep when my bedroom door creaked open. A shaft of light punctured the semidarkness. “Annie? Time to go shopping.” Mom’s voice, as joyous as a meadowlark.

Jeez, 6:20. I pulled the sheet over my head. “Up and at ’em, sleepy head,” Mom said in a stage whisper. “Joslyn’s has an early-bird sale on fall clothes. The bargains go fast.”

“Try this, Annie—A woman can’t go wrong with pink!”

After a bowl of All-Bran, a piece of toast, and a three-minute shower, I dashed off with Mom to her favorite mall. At 6:55, Mom was chattering away, me dragging behind. I hated shopping. She embraced it as a fundamental component of healthy living, like her daily walk.

Still, I chafed at being her Barbie, at being dressed to fulfill her aspirations. On the other hand, she was an eager, helpful valet, a trusty escort in unfamiliar territory.

By the end of an exhausting day hoofing through two malls, Mom outfitted me with a wardrobe of suits, dresses, blouses, and skirts that guaranteed I’d be a fashion plate at Glendale Union High.—Ann

Terry: Day One in Arizona—A Job and a House!

Wednesday, 19 August 1964, Glendale, Arizona.I eased into a parking space near my first prospect, the Glendale News, readied my résumé and portfolio of published articles, and swung the car door open.

The Glendale News snapped Terry up in 45 minutes.

Whoosh! A blast furnace singed my eyes and lungs. Time and temperature on the bank marquee: 3:14 p.m.; 106 degrees. Jesus, what was I doing there? In August!

Forty-five minutes later, I had a job: reporter for the Glendale News, $4,500 a year, with grand prospects ahead. My new boss would complete the paperwork to buy out the competing Glendale Herald by November 1. We’d become the Glendale News-Herald, expand from weekly to biweekly and then to a daily within a year. I’d work five days a week, covering city hall, police, courts, local politics, school board—all the major hard-news beats.

By nightfall, I’d found a house—not an apartment or basement cell, but a house, a charming one-room bungalow, at $60.10 a month, an easy stroll to the newspaper office on the town square.

The next morning I’d head back to Center, pack, return the following week, and begin my newspaper career Monday morning, August 31.

Annie would be coming that week. I called her. “A job and a house? On your first day?” she said. “I’m impressed.”

So was I. We were on our way!—Terry

The Joys of Being a Mom

Friday, August 21, 1964, Albuquerque. In the midst of my countdown to Arizona, Mom insisted I visit Cindy Gomez, the daughter of a friend of hers. Cindy had recently given birth to her first child, and upon greeting me, she launched into a tale of the delivery, as if it had been a big-screen spectacular.

“Oh, Ann, it was so exciting. We barely made it to the car when my water broke—oh my, like a rainspout in a cloudburst down there. The car’s a mess. By the time we got to the hospital, I had dilated six centimeters. Did you know you open up ten centimeters down there? That’s four inches!”

She formed a circle with both hands and held it between her legs. “Amazing, isn’t it?”

Gretchen had gone to the hospital by herself. When Terry and I visited her, she had spoken lovingly about her baby. No gory details, just unrestrained happiness at having brought a child into the world. Watching Cindy cuddle her baby, I sensed the angst Gretchen must have felt. She hadn’t decided whether she would give it up for adoption. Having a child should be a time of joy, not emotional pain and shame.

“Isn’t that amazing?” Cindy said.

“Huh, what?”

“My episiotomy.” With a grimace, she adjusted her derriere on her doughnut pillow and gestured downwards. “I needed only four stitches.”

“Stiches? For what?”

“You know, they cut you down there. After that, the baby squirts right out.”

The image jolted. A masked doctor hones his scalpel, slices her tender underside, and then drops his tool of torture to catch a squirming baby! Something else Gretchen didn’t mention.

I was not ready for this marriage thing. “Oh, yeah, Cindy. Yes. Really amazing.”

“Being a mom is fantastic, though. This little tyke is such a delight.” She tugged up her blouse and snapped open her bra. An engorged nipple popped free. She maneuvered the baby to her breast. “There, there, baby, you are hungry, aren’t you? Have some mommy juice.”

The baby latched on. Cindy winced, “Go easy, sweetie.” The baby went after it like a starving calf.

Cindy looked up and beamed. “See what I mean?”—Ann

Mom’s Parting Message: Be a Good Girl in Glendale!

Monday, August 31, 1964, Albuquerque. I left for Arizona, not alone, but with Mom beside me. She would talk to me, drive if I got tired, and help me find an apartment. “Besides, I hate to see you leave,” she said. I couldn’t say no.

That afternoon in Glendale, Arizona, the moment we toured the Maryland Club Apartments I knew I’d found my new home. Close to Glendale High. Furnished. One bedroom. Cozy kitchen. A complex that pulsed with teachers and young professionals. I could lounge around the pool with colleagues on weekends, join in activities—like the luau planned for September—designed to turn these apartments into a real neighborhood.

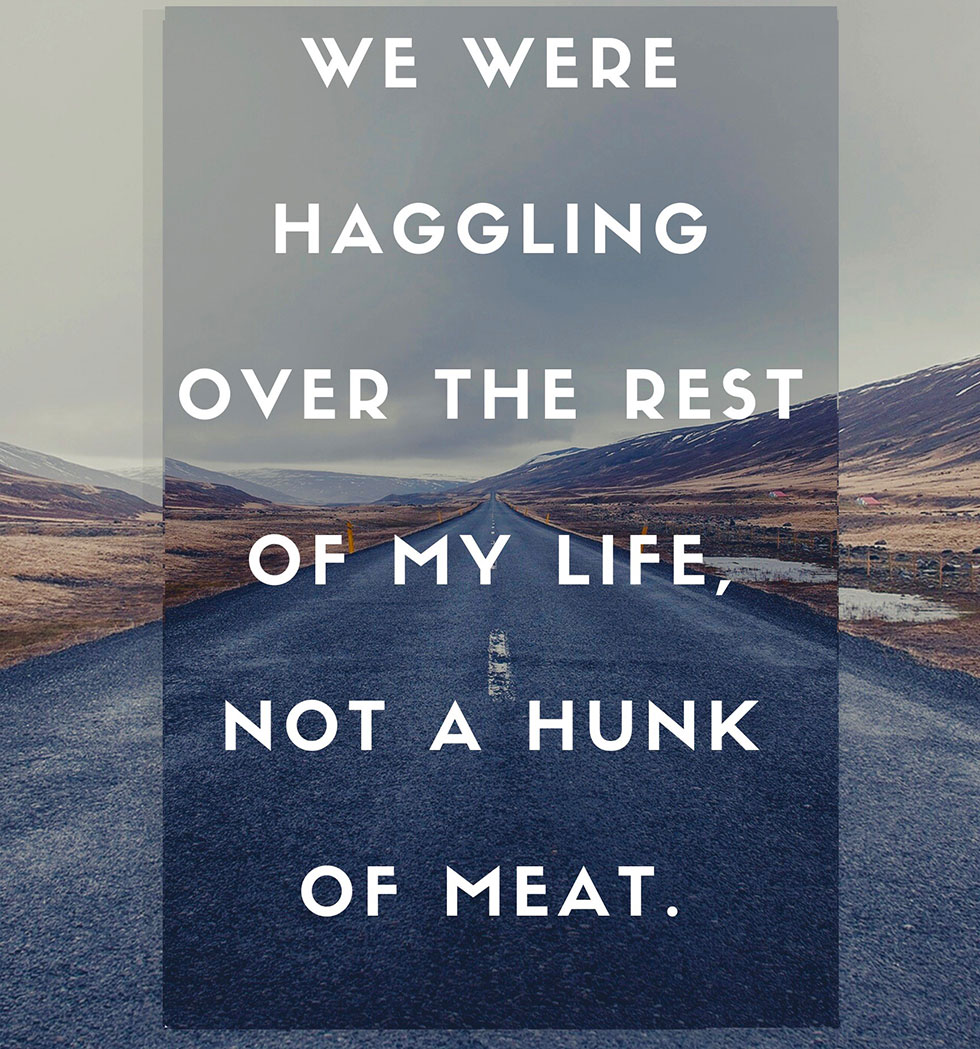

In our time together, Mom had laid out her and Dad’s expectations for my behavior as a teacher—in softball questions, offhand remarks, and hints seeded into our zigzag conversations. Sex lay at the core of their worries, lurking underground, verboten as a discussion topic. She warned, “Don’t do anything that would reflect badly on yourself or your upbringing.” In Mom-speak, Do not invite men into your apartment. Corollary: Do not have sex.

In June their worry no doubt had been Jack, in Europe. Now it was Terry, too close for comfort, living in the same town. On Wednesday, as I drove her to the airport for her flight home, she campaigned—in her sweetest voice—against my having anything to do with Terry. He wasn’t right for me, she said directly, forcefully, openly. To my astonishment, she resumed her crusade with a letter that weekend:

You can’t be having Terry in your apartment, helping you grade papers, and such. In fact, he shouldn’t be hanging around all the time—it won’t look good. And, Ann, please don’t ask him to the apartment luau. You will lose other opportunities if he is too much in evidence.

With your charm, personality, beauty, wit, background, you can command the best. Stick to your high ideals, your religious beliefs—and don’t be swayed by superficial things (such as a “gift of gab” and a jolly time you can have with someone). Look deeper and see the real man.

Oh, yes, one more thing: you have been used to good things that money can buy in life. Find yourself a man who can take care of you.

I was a dutiful girl. I didn’t want to disappoint, except for one small detail. We were haggling over the rest of my life, not a hunk of meat. Who was out of step with whom? Was I wrongheaded? Or were they?

Given that I loved both men, it was about the best match of our goals and values. And the wrenching decision of what path I would choose for my own future.—Ann

Ann’s Decision at Last: I can’t marry either one of you

Sunday morning, September 6, 1964, Glendale. My focus was clear. I couldn’t marry Terry or Jack. Not right away. I had to tell them, but how could I carry it off without hurting either of them?

I started with a letter to Jack—a trial run—writing was easier than stuttering things out face-to-face with Terry. Still, my letter was awkward.

Then I had to face Terry. By midafternoon, I was pacing my living room, jittery as a fourteen-year-old on a first date—long before he joined me for dinner.

Ann “buried” in the Glendale News.

Over dinner, Terry went on about the upcoming week’s stories, his plans for turning the News into a “real” newspaper. I buried myself in the paper, mustering the occasional “uh-huh” until he stopped midsentence and cocked his head. “You’re too quiet. What’s up?”

“Ter, I can’t do it, not right now,” I told him—gently, lovingly, but emphatically. “I’m simply not ready to marry anybody.”

Instantly, he clammed up, a gloomy replay of Jack as stone statue in Landshut, when I first told him about my feelings for Terry.

Now what? He had to understand my decision. Love wasn’t the issue. I did love him. I simply wasn’t ready to marry. Europe had taught me that. While I had loved the time with Jack, I also took pleasure in (and was amazed by) what I did by myself. I didn’t need to depend on my family or a husband.

“I don’t mean forever,” I said. “I need time on my own so I can be sure, that’s all.”—Ann

Sunday night, 6 September, 1964, Glendale. My mind was reeling. She turned me down. We were talking, chatting like normal. She went silent. Then bam. “No, Ter, I can’t.”

Was it Jack? I didn’t know. She didn’t mention him. She did say “your military views” and “I need to be on my own.” I couldn’t remember what else. It didn’t matter, the exact words. It was over. Halfway through a sandwich. Our first week together in Glendale, and it was over.

What the hell was I going to do now? In Glendale, Arizona. Alone.—Terry

End of the line for the Rendezvous Log: What Now?

Monday, 7 September 1964, Glendale. I awoke a stranger in a foreign land, an orphan abandoned in the desert.

Sunday night, she’d dumped me. My Peace Corps dreams dashed. Hopes for marriage squelched. Friends nonexistent. The draft menacing.

At least I had a job. Or I would until the draft board caught up with me.—Terry

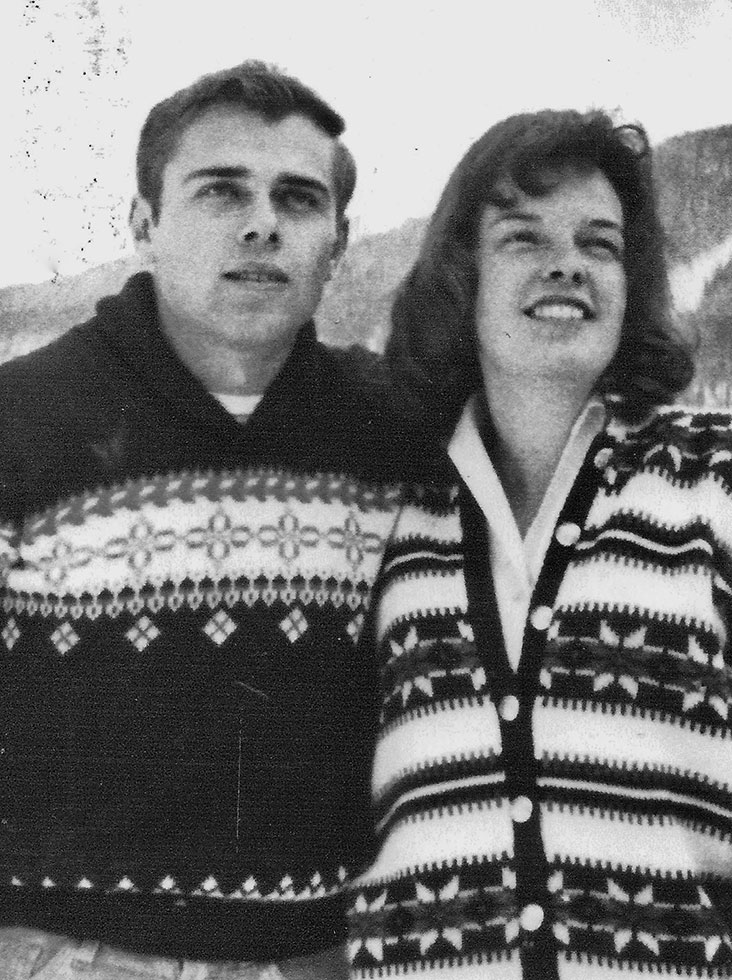

Terry & Ann, March 12, 1965—the day before our wedding

Editors’ note:

Obviously, September 6, 1964 wasn’t the end of the story: after all, we’re co-authors of A Rendezvous to Remember, and we now share the same last name.

So what happened after that painful night in September 1964?

Lots, actually: more heartbreak, more indecision, and reconciliation. But also family opposition; an anxiety-filled battle with the draft board; and more heartache than we could have imagined; as well as Jack’s story, and eventually the opportunity to fulfill that long delayed dream of becoming Peace Corps Volunteers.

We won’t chart that rocky road here: you’ll find it laid out in vivid detail in the rest of the book. Tell you one thing, though: it’s a lot easier to read the story than it was to live it.

Sign Up for News Flashes

Please keep in touch! And to be notified for events around A Rendezvous to Remember and other news from us, please sign up. Our promise? We won’t sell your address to anyone or clutter up your inbox with junk.