I couldn’t make the dedication, but at least today we’ve got C-Span. Only one of the speakers was back on stage from 48 years ago – John Lewis. But we had folks who were there: among them, Diahann Carroll, Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young, Dan Rather, a wonderfully fiery Al Sharpton. Plus the two King kids, all grown up now, but alas, not nearly the speakers their father was.

The President spoke, too, and his speech reaffirmed my faith in him. He neatly tied MLK’s message to today’s hurdles, urged us not to give up in the face of recalcitrance, to fight on, never to lose hope. What an optimist, particularly given his battle with Congressional Republicans, who seem willing to sink the Ship of State itself, so virulent is their intent to run the Captain off the plank. Or keelhaul him.

They played MLK’s “I Have a Dream” on the giant screen. His voice still resonates, and the panning cameras showed again how huge the crowd was. (Would that we could fill Wall Street with such a crowd!) It also reminded us that 1963’s March on Washington was a cry for jobs, as well as freedom. How ironically timely!

I missed the original March on Washington –I was off in back-roads Colorado . . . actually I was on the road, wending my way over a narrow mountain pass en route home, listening to him on the radio.

I wasn’t the only country bumpkin moved by King’s speech. Take Rick Sanders, the protagonist in my novel, Soda Springs: Love, Sex, and Civil Rights. He was farming that day, caught up in thoughts of how difficult life had become, about . . .

No, wait, King’s “I Have a Dream” changed Rick’s life forever. Rather than tell you how, let me show you: the following is from Soda Springs. Here, you can read it for yourself:

Wednesday morning, the belching Case drowned out Rick’s anguish over the barrio’s defeat. But then, the tractor’s beat began hammering out strike chants: “two, four, six, eight, who we gonna liberate? Cis-co, Cis-co, Cis . . .”

A jackrabbit bounded alongside the tractor and zigzagged into uncut alfalfa; next round she would be in his path. The tractor was Soda Springs: relentless.

By noon, clouds formed over the Sangres and rolled toward him. He chomped down two baloney sandwiches as he drove. Even if he finished mowing before it rained, he wouldn’t have time to rake, let alone bale. No matter what, he would leave Friday for Cornell.

Midafternoon, shiny rain splotches dotted the hood. Lightning flashed. Thunder crashed, and rain pummeled him. He raced for the shop.

He flipped on KSCV: Lil Baker’s inane clubs report, “Valley Do-ins.” He jockeyed the radio to KOA-Denver: a pitch for Chevys. Then, mellifluous Walter Cronkite came through the static. “Mr. Randolph has come back to the podium, he . . .”

Rick fussed with the dial. “. . . presenting Miss Mahalia Jackson.” That civil rights rally in Washington? He checked Pops’ grimy wall calendar.

August 28. He had forgotten.

Mahalia Jackson sang a cappella, and a roar drowned out the last echoes of her song. Cronkite said it was hot and two hundred thousand people had been crammed into the mall for hours. A rabbi came to the podium. Rick imagined Charlie popping jokes, Deb beside him, all goo-goo eyes.

Outside, the rain let up, but the yard oozed goo. No more mowing today.

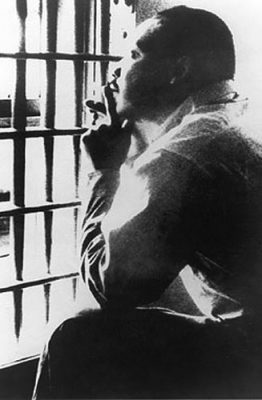

Cronkite again: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. next. Rick wiped down the Case as if it were a prize foal. Through the static, King cried, “Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells.”

Rick chimed in, “And others from sopping wet alfalfa fields.”

King said he dreamed about the red hills of Georgia. “My dream is that Concha will come with me to the gorge-studded hills of Ithaca,” Rick replied. Man, that was stupid to ask her to live with me. She’ll never speak to me again.

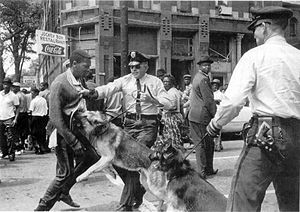

Even over static-encrusted KOA, King wrung nuance from every syllable, turned pauses into insights. He’d been jailed, beaten, stabbed. Yet, he dreamed on.

“With this faith we will be able to work together, pray together, struggle together, go to jail together.” Little shouts of joy punctuated his words: Amen. Amen, Lord.

“Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York . . . from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.”

Wow, King zipped from Washington into Pop’s very shop and shifted into overdrive. The static melted away.

“From every mountainside, let freedom ring . . . from every village and hamlet, from every state and every city . . . speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, we are free at last!’”

King’s dream rolled down from Lincoln Memorial over the crowd, crossed the Sangre de Cristos, gathered in the San Juan foothills, and came to rest in a tiny cementerio beside the old Catholic church at Las Piedras.

Every village and hamlet. Protestants and Catholics. Mexicans and whites. Farmers and farmworkers. Freedom together, not separately.

“Continue until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Keep it up until you free the Cisco Kid, until justice hunts down Tommy’s murderer.

Rick knew the barrio couldn’t right the wrongs of history in one summer; racism ran too deep. But they had to struggle on. Martin Luther King demanded it. Soda Springs’ battle had only begun, and Dr. King called on him personally to join him: You out there in the Rockies, in Soda Springs, Colorado. You, Rick Sanders.

At last, the summer made sense. Rick’s mission wasn’t in Birmingham, nor Washington, D.C. Go back to the Rockies, to Sanders Farms in your little village of Soda Springs. That’s where he was meant to be. And not only for the summer. Dr. King committed himself to a cause greater than himself; that was his dream.

Rick had failed this summer in part because he dreamed of lust, not justice. He had to stay and fight with Concha, even if it cost him his family and earned him white Soda Springs’ eternal hatred. “So long, Cornell. It’s been nice.”

A double rainbow broke through the haze. Rick’s hay lay water-logged. At best, raking was two days away. No matter. He could rake and bale next week.

“Thanks, Martin, if nothing else, I’ll get Pops’ hay up this summer.” He sharpened the mower blades and gassed the tractor. He had to be ready for every ray of sunshine.

Rick raced for town to deliver his vision to Concha.

En route, he sobered up. For a few euphoric moments, Martin Luther King trumped reality. Concha would eviscerate him. Am I some puta to live with you in sin?

Worse, she would have told Elias and Nacho. You gringos beat us, so now you dare ask Conchita to be your mistress?

They would come for him with Espino’s cutters, brandishing their razor-sharp lettuce knives. Nah, he was being melodramatic.

He pulled up to Concha’s house, and a new thought struck. What if she chose Chicago? He would not only lose her, he would be left behind to face the cavalry by himself.

Today is a day to celebrate. It’s Martin Luther King’s birthday, Sunday, January 15.

Today is a day to celebrate. It’s Martin Luther King’s birthday, Sunday, January 15. We’ve waited six weeks to dedicate the new Martin Luther King National Memorial on the Mall. No earthquake today. No hurricane. No rain. Today, a crisp fall morning in D.C. October is a good time to be in D.C., and the memorial is another reason to revisit Washington.

We’ve waited six weeks to dedicate the new Martin Luther King National Memorial on the Mall. No earthquake today. No hurricane. No rain. Today, a crisp fall morning in D.C. October is a good time to be in D.C., and the memorial is another reason to revisit Washington.