It’s a milestone birthday week for the Peace Corps: The big Six-Zero!

Sixty years since September 22, 1961, when JFK signed the legislation creating the Peace Corps.

Sixty years of memorable events: the first 51 Volunteers arrived in Ghana in the fall of 1961; the Peace Corps expanded rapidly—500 volunteers in nine countries by the end of that year, 15,000 by June of 1966; service extended to 142 countries.

Sixty years—240,000-plus Volunteers!

But today, the Peace Corps lies in suspended animation, a victim of Covid-19. No Volunteers are serving abroad. None. Zero.

In eight days, beginning on March 16, 2020, the Peace Corps brought every Volunteer back home to the U.S.— 6,982 of them. None have gone back—at least not officially.

Despite the hasty (but well-executed) exit, the Peace Corps lives on. There’s staff in the Washington D.C. headquarters. The Biden budget sets aside $410.5 million for Fiscal Year 2022, and the agency says it will send Volunteers to Belize in 2022. But today, no Volunteers are in the field. Nothing’s permanent about a new startup date.

What a loss! Not only to the world, but to a new generation of Americans.

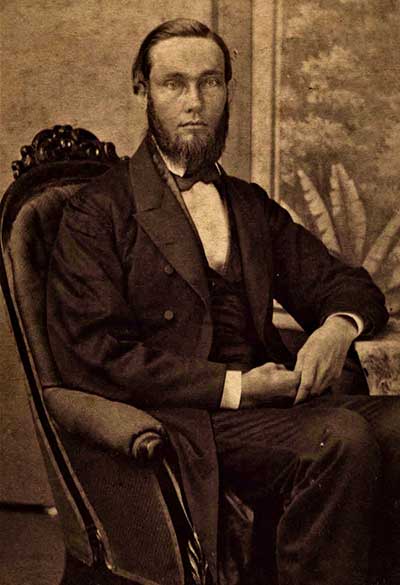

Annie and I spent seven years in the Peace Corps—two as Volunteers in the Philippines; three as the country co-directors of programs in the Solomon Islands, Kiribati, and Tuvalu; and for me, two years in the Washington D.C. headquarters.

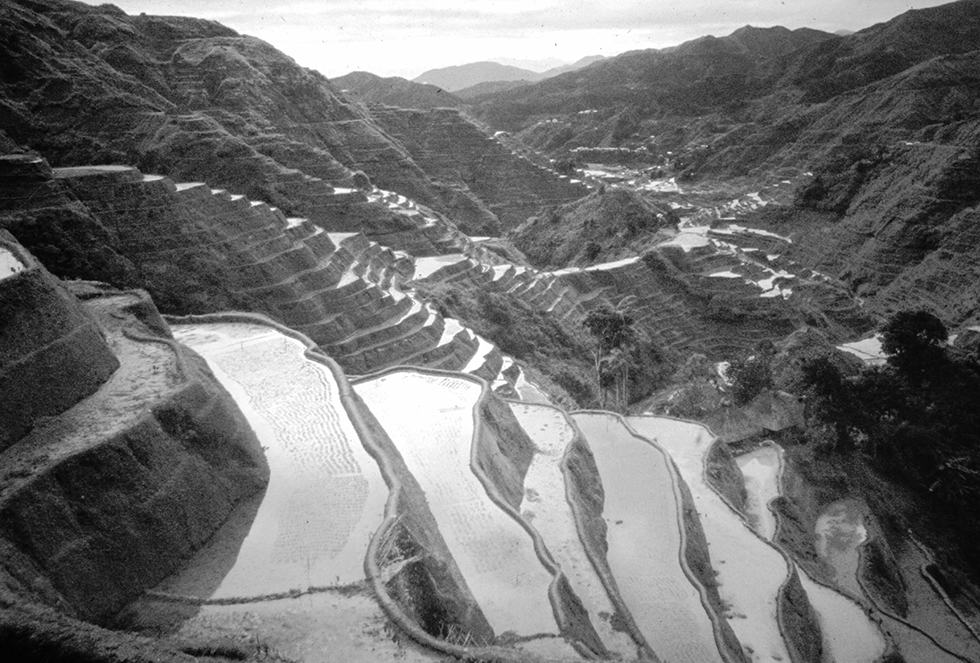

A Peace Corps Honeymoon: Two Years in the Philippines

For us, it seems like yesterday when Annie and I stepped from that Philippine Airlines flight onto the tarmac in Tacloban City, Leyte, one bright September day in 1965. We were newly minted Volunteers, six months married—Tacloban would be our home for the next two years.

I arrived in the Philippines a budding young newspaperman—with a journalism degree and a short stint as editor of the Glendale (AZ) News-Herald—and with hopes of someday owning my own small town newspaper. Annie had a BA in English and a year’s experience teaching English at Glendale Union High School. She wasn’t as clear about her long-term goals.

Those two years changed our lives forever—as Peace Corps service has done for thousands of other Volunteers. What an education!

Suddenly we were strangers in a wonderfully “strange” land. After our three months of intense training, we arrived able to carry on a basic conversation in Tagalog—but, alas, they spoke Waray-Waray in Tacloban. Challenge One on Day Two: start all over—learn yet another language.

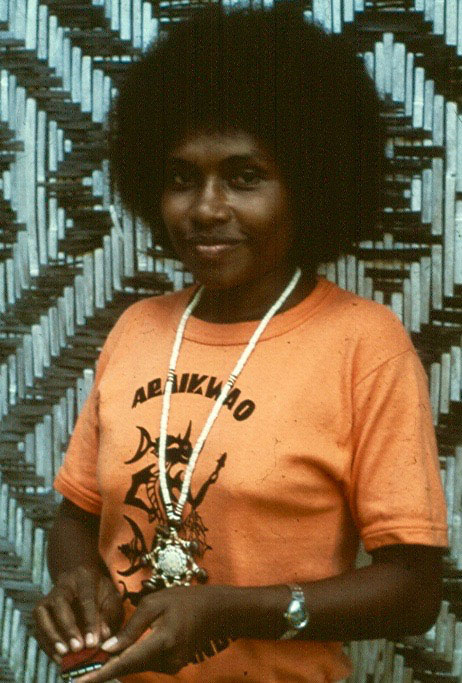

Annie with Guillerma Villacorte

My assignment was to instruct my Filipina co-teacher in the latest techniques for teaching English as a second language. My co-teacher, Guillerma Villacorte, had been teaching for twenty years. It was she who taught me how to teach—as well as how to speak Waray-Waray.

We quickly learned that we Americans were too blunt, too single-minded, too rushed to fit easily into Filipino society. And that physically, we looked different from everyone else—we stood out like sore thumbs. People noticed what we did . . . or didn’t do that we should have. We crossed boundaries we couldn’t see and violated taboos we didn’t realize existed.

But we listened, and watched, and learned, and slowly came to realize that the “American way” isn’t the only way or necessarily the best way to live one’s life.

After the Philippines, I went to grad school—no longer in journalism, but to study community organizing and intercultural change.

Ten years later—after hard-fought battles against racism and poverty in the Chicano barrio in my hometown and a PhD in rural development, the Peace Corps called us again.

Adventures Anew: Three Countries in the South Pacific

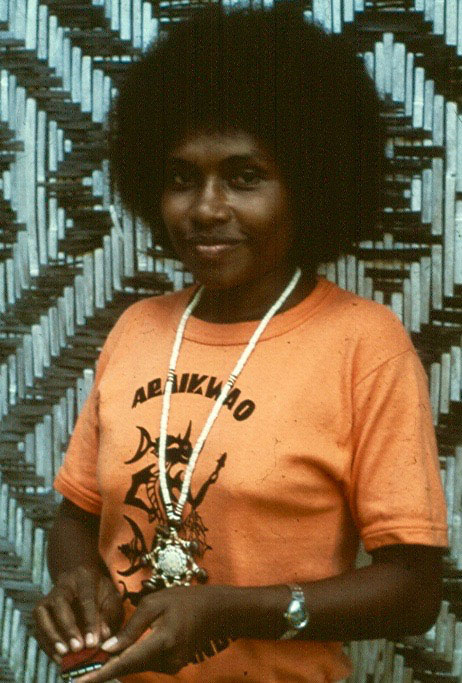

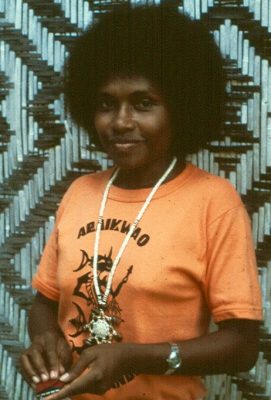

Carolyn Siota, administrative assistant extraordinaire

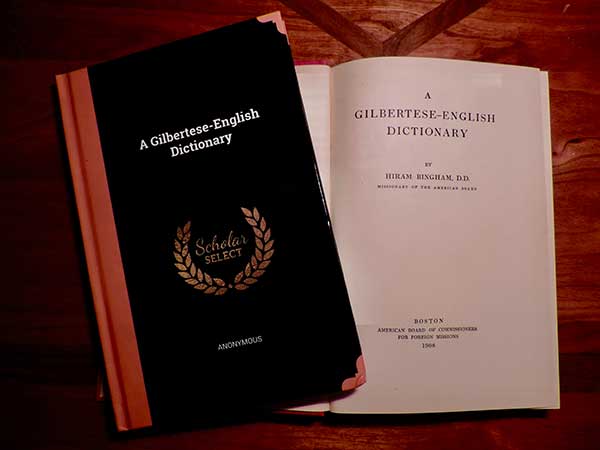

This time, as country co-directors of Peace Corps operations in the three strikingly different cultures of the Solomon Islands (Melanesian), Kiribati (Micronesian), and Tuvalu (Polynesian), Annie and I plunged again into new life styles, new languages, new adventures as foreigners in wonderfully different lands. And we realized again—thanks to Carolyn Siota, our incredibly talented administrative assistant—that without local guidance, we’d never accomplish anything overseas.

After three years in the South Pacific, wonder of wonders, I ended up in Peace Corps’ Washington, DC headquarters. Talk about strangers in a strange land! But a fascinating one—Peace Corps/Washington was peopled with remarkable, talented, hardworking colleagues. It was bureaucracy at its best.

Our five Peace Corps staff years reaffirmed those lessons we first learned as Volunteers in Tacloban City: that we Americans were too blunt, too singleminded, too rushed. In the Solomons, we looked different from everyone else—again, we stood out like sore thumbs. Again we crossed boundaries we couldn’t see, and violated taboos we didn’t realize existed.

But again we listened, and learned, and broadened our lives and our outlook.

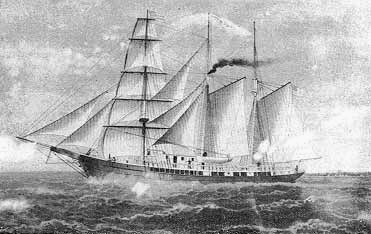

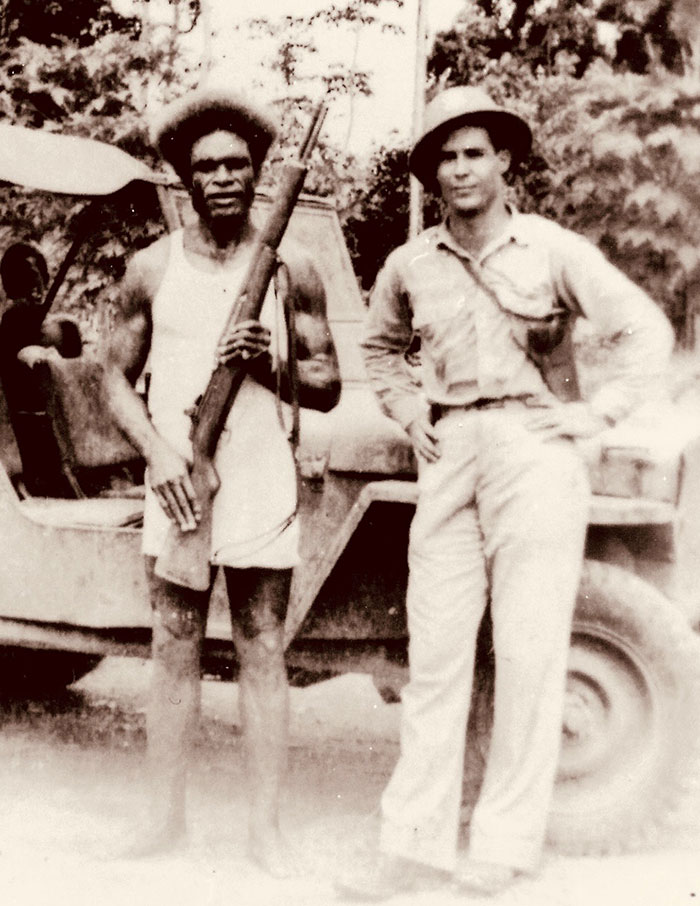

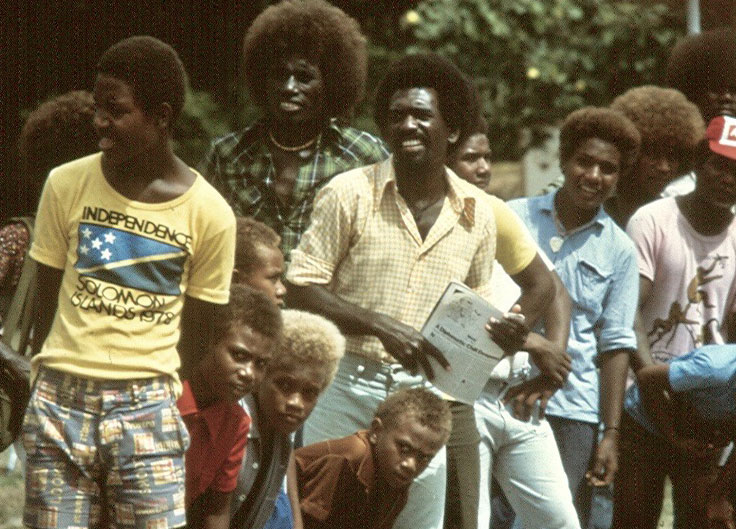

A Solomon Islands village on Guadalcanal

Once more we survived the challenge of being immersed in settings where we didn’t know the languages—gesturing, grunting, trying to extract meaning from strange sounds. We traveled to remote villages where meals consisted of fire-roasted sweet potatoes and boiled veggies that looked a bit like collard greens, but served on banana leaves, and eaten with our fingers. We learned to sleep on sharp-edged slatted floors, or two of us in a furrowed single bed.

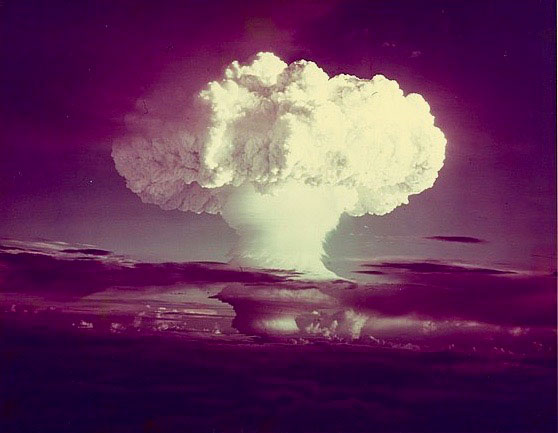

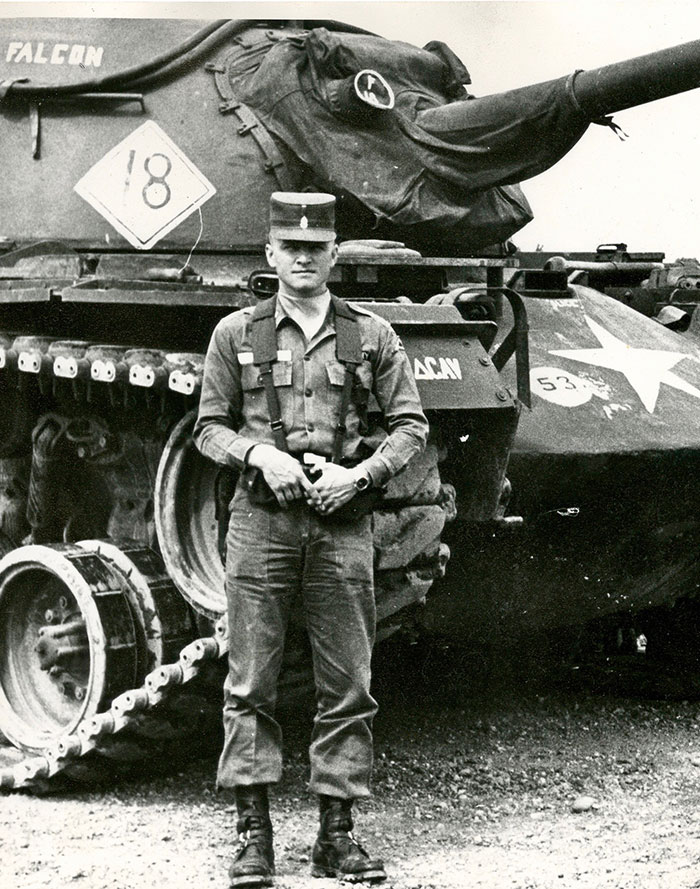

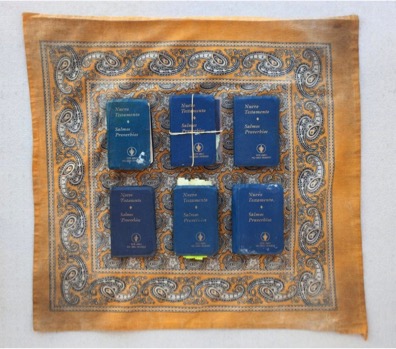

And most of all, we reaffirmed our joy in travel—especially to out-of-the-way places. Like Plum Pudding Island, where daring Solomon Islanders rescued JFK after the Japanese navy sunk his P-T boat in WWII; to Funafuti, Tuvalu, where Louis Zamperini (the subject of Laura Hillenbrand’s remarkable biography, Unbroken) took off on his fateful flight; to WW II battle sites on Tarawa and Guadalcanal.

Lessons for Life: the Joy of Unique Challenges

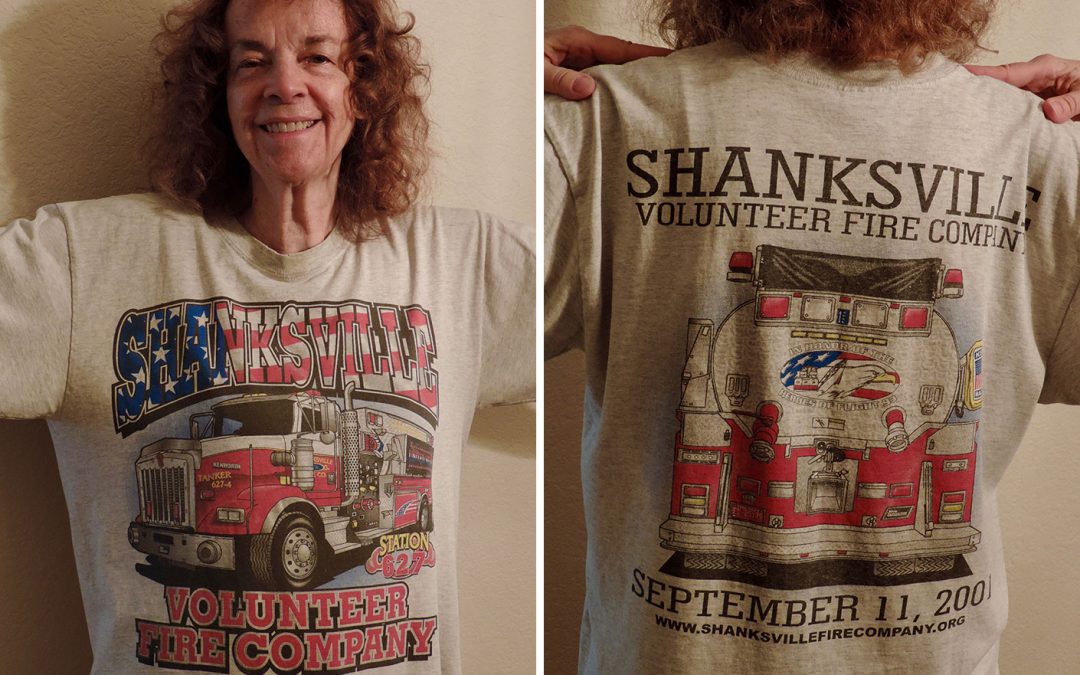

Our twin beds in Jah-Deh—both colorful and comfortable

Our Peace Corps experiences served us well on later trips—like dinner in our Quecha-speaking host’s smoky, dim, candle-lit kitchen on Amantani Island in Lake Titicaca; or the night we slept on the floor in the Chin village of Jah-Deh in the mountains of western Myanmar; and the wind-swept, ice-cold room in the hotel under renovation in Sa Pa, Vietnam.

And our lives have been enriched by the folks we’ve met:

- The Japanese family who took us in because we couldn’t articulate that we weren’t really dirt-poor—they served us dinner in their home, and put us up for the night;

- The owner of a small hotel in Wasserburg, Germany, who sent a bottle of wine to our room because we were from Las Vegas, and her daughter was in our city that very night celebrating her 21th birthday;

- The teachers we worked with in Ban Pa Ngio, Thailand, who took us into extraordinary temples, and farm fields, and local markets on their days off.

Annie makes a friend in Yangon, Myanmar

The Peace Corps imbued us with that irrepressible urge to travel, the desire to mix with people different from us—in language, skin colour, history, education, living conditions . . . The realization that America isn’t the center of the universe . . . A fresh awareness of some of our own biases, values, desires that are strikingly different.

We didn’t accomplish world peace in our seven Peace Corps years—and we didn’t really expect to. But we did plant some seeds, and helped guide a few students and some of our Volunteers into fruitful projects. And we made some lifelong friends.

But most of all, our Peace Corps years reshaped our own lives. They made all of us—Volunteers and staff—citizens of the world, and, we think, better persons.

That’s the real contribution of the Peace Corps. For that alone, let’s hope this 60th anniversary leads us to overcoming Covid-19 and getting Volunteers back into the field.—Terry

From our years in the South Pacific, Terry and I also know something about cross-cultural and interracial romances. We knew Peace Corps Volunteers and other expats who overcame such barriers to love. Like any other romance, some married and thrived. Some didn’t.

From our years in the South Pacific, Terry and I also know something about cross-cultural and interracial romances. We knew Peace Corps Volunteers and other expats who overcame such barriers to love. Like any other romance, some married and thrived. Some didn’t. Mom and Dad brought me up expecting to obtain a college degree and believing I could do whatever I set my mind to. In the ferment at the University of Colorado, the nascent movement for women’s equality seemed a natural progression to me and my gal pals, not an anomaly.

Mom and Dad brought me up expecting to obtain a college degree and believing I could do whatever I set my mind to. In the ferment at the University of Colorado, the nascent movement for women’s equality seemed a natural progression to me and my gal pals, not an anomaly.

Sexual misconduct? Say it’s not so! When U.S. Sen. Al Franken and then Prairie Home Companion host Garrison Keillor were outed for sexual misconduct in November 2017 by new accusers, my inner lioness roared, “No! It can’t be!” I wanted to race into the fray, snatch them out of danger. Me. The Zero Tolerance woman, the “Kick’em in the nuts” gal.

Sexual misconduct? Say it’s not so! When U.S. Sen. Al Franken and then Prairie Home Companion host Garrison Keillor were outed for sexual misconduct in November 2017 by new accusers, my inner lioness roared, “No! It can’t be!” I wanted to race into the fray, snatch them out of danger. Me. The Zero Tolerance woman, the “Kick’em in the nuts” gal. But I didn’t know whether these men were actually different, not for a fact. In addition, I hadn’t objected to the summary dismissals of the many accused men who had preceded them. My discomfort around these new accusations grew after The Washington Post revealed an organization that tried to run a sting operation by planting a fake story about Roy Moore that could then be used to embarrass the newspaper.

But I didn’t know whether these men were actually different, not for a fact. In addition, I hadn’t objected to the summary dismissals of the many accused men who had preceded them. My discomfort around these new accusations grew after The Washington Post revealed an organization that tried to run a sting operation by planting a fake story about Roy Moore that could then be used to embarrass the newspaper. But if we hesitate, if we wait for the slow grind of justice, does that leave the predators free to prey on other women? Shouldn’t we hold our public officials and our media to a higher standard? Shouldn’t we work quickly to protect young girls from child molesters? What if the sexual misconduct was a one-off . . . or happened decades ago? My head spins with questions.

But if we hesitate, if we wait for the slow grind of justice, does that leave the predators free to prey on other women? Shouldn’t we hold our public officials and our media to a higher standard? Shouldn’t we work quickly to protect young girls from child molesters? What if the sexual misconduct was a one-off . . . or happened decades ago? My head spins with questions.

Jose Rizal isn’t an author you run into every day. Nor is his 1891 novel, El Filibusterismo, at the top of today’s best seller lists. But there he was, in sepia grandeur, on this book review site, Bookingly Yours How could I not be intrigued?

Jose Rizal isn’t an author you run into every day. Nor is his 1891 novel, El Filibusterismo, at the top of today’s best seller lists. But there he was, in sepia grandeur, on this book review site, Bookingly Yours How could I not be intrigued?

They listen on. The announcer says Medgar Evers has died.

They listen on. The announcer says Medgar Evers has died. Sunday morning, June 16: Rick and Ginny do their skit -– Rick as Medgar and Ginny as assassin, complete with Ginny’s father’s 30-30! The high school kids go wild. Discussion ensues.

Sunday morning, June 16: Rick and Ginny do their skit -– Rick as Medgar and Ginny as assassin, complete with Ginny’s father’s 30-30! The high school kids go wild. Discussion ensues. Let’s toast The Help and author Kathryn Stockett’s success. OK . . . now let’s drink to Skeeter, Aibileen, Minny, Celia and the whole cast of the movie for bringing Kathryn’s creations visually to life. As a chaser, let’s down a grand old sherry for all these winners, both on the bookshelves and the big screen. Here’s why:

Let’s toast The Help and author Kathryn Stockett’s success. OK . . . now let’s drink to Skeeter, Aibileen, Minny, Celia and the whole cast of the movie for bringing Kathryn’s creations visually to life. As a chaser, let’s down a grand old sherry for all these winners, both on the bookshelves and the big screen. Here’s why: Before I built a wall I’d ask to know What I was walling in or walling out.

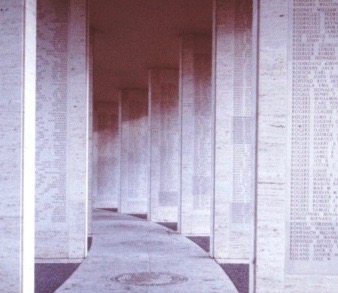

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know What I was walling in or walling out. Glory be, I finally saw The Wall: you know, the one that keeps the Mexicans out of America, thus keeping us safe from the cartels and their hit men. Or more to the point, the one that prevents all those shiftless Mexicans from coming here to

Glory be, I finally saw The Wall: you know, the one that keeps the Mexicans out of America, thus keeping us safe from the cartels and their hit men. Or more to the point, the one that prevents all those shiftless Mexicans from coming here to