An Uneasy Peace at the Peace Corps

Powerful book and documentary evoke powerful memories

Terry, supplement to A Rendezvous to Remember, Ch 15: Last Act in London, August 1964, Center, Colorado; June 1981, Washington D.C.; and 2009, Hanoi, Vietnam

The Hanoi Hilton leaps from the pages of chapter 3 in Geoffrey Ward’s The Vietnam War, based on the Ken Burns-Lynn Novick PBS series. I come to this date: August 4, 1964. Aeii, the memories!

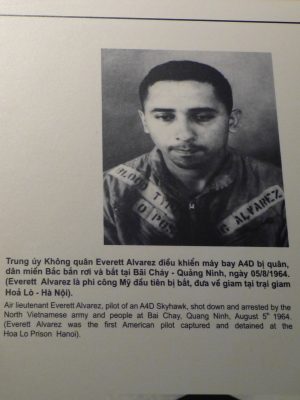

That day, the US began bombing North Vietnam. And that day, the North Vietnamese shot down their first American fighter jet. The pilot: Lt. Everett Alvarez, 26, from Salinas, California. Everett would spend the next 8½ years in prison, much of it in the infamous Hanoi Hilton. He was America’s longest-held prisoner of war in Vietnam.

Also on that day, August 4, 1964, I was at home in Center, Colorado, two months out of college, ten days from entering the Peace Corps, and hoping Ann Garretson would accept my marriage proposal—sent to her airmail while she was traveling Europe with her West Point lieutenant in his 1963 Corvette Sting Ray. Weeks had passed since I had proposed.

She hadn’t answered. I couldn’t stand it. I sent my plane ticket back to the Peace Corps . . . and waited for her answer. It came a month later: “No.” (Both Peace Corps and marriage worked out later, but those are different stories.)

Fast Forward to June 1981: The Long Shadow of the Hanoi Hilton

Lt. Everett Alvarez, as POW

Everett Alvarez takes over as Deputy Director of the Peace Corps in Washington, D.C. Suddenly, he’s my supervisor’s boss.

Alvarez and I have nothing in common—he’s military to the core, a dyed-in-the-wool conservative, and he doesn’t know squat about the Peace Corps. On the day he joins the staff, I have six years of experience with the Peace Corps, including two years as a volunteer in the Philippines, three years as the country director in three South Pacific nations, and a year on the Washington staff. I’m one of those people Alvarez spurns as “ex-volunteers who had signed on for permanent jobs at headquarters when their field tours were done.”

All of us—he will write in his first book, Chained Eagle—are a bunch of young idealists, anti-war activists, and irresponsible spenders, as well as “something less than skilled managers.” It’s clear that he doesn’t trust us. Nor we, him. In fact, we on the Washington staff are anything but of one mind—in our politics, training, and experience.

Nor are we slackers: Many of us log numerous ten- and twelve-hour days, and plenty a weekend. By contrast, Alvarez accepts his full-time Presidential appointment as deputy director, then enrolls in law school, and spends less than full time with the Peace Corps. My office is down the hall from his, but Alvarez is a loner. He doesn’t mingle. We do our jobs; he doesn’t interfere. We scarcely hear him say a word, no more than a mumbled “morning” when we pass in the hall.

Invisible POW Ghosts Hover

One afternoon, not long after he moved into his office, I find myself alone with him in the john. He stands slumped forward, his eyes glazed over. A deep, sad sigh arises from what seems like the depth of his soul.

Thirty Years Later, a POW Uniform Triggers New Understanding

In 2009, nearly 30 years later, I come across Everett’s prison uniform on display in the Hanoi Hilton in Vietnam. I finally get a glimpse of the brutality he experienced, and begin to understand the meaning of that long, heart-wrenching sigh. The Vietnam War—both book and the PBS series—bring those memories flooding back.